By Pam Knox

In October 2021, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) announced that a La Niña event had begun. It has an 87% chance of continuing through the winter. Since that time, the event has affected weather across the world, including many crop-growing areas of the United States. This article looks at what La Niña is and how it affects local climate.

LA NIÑA VS. EL NIÑO

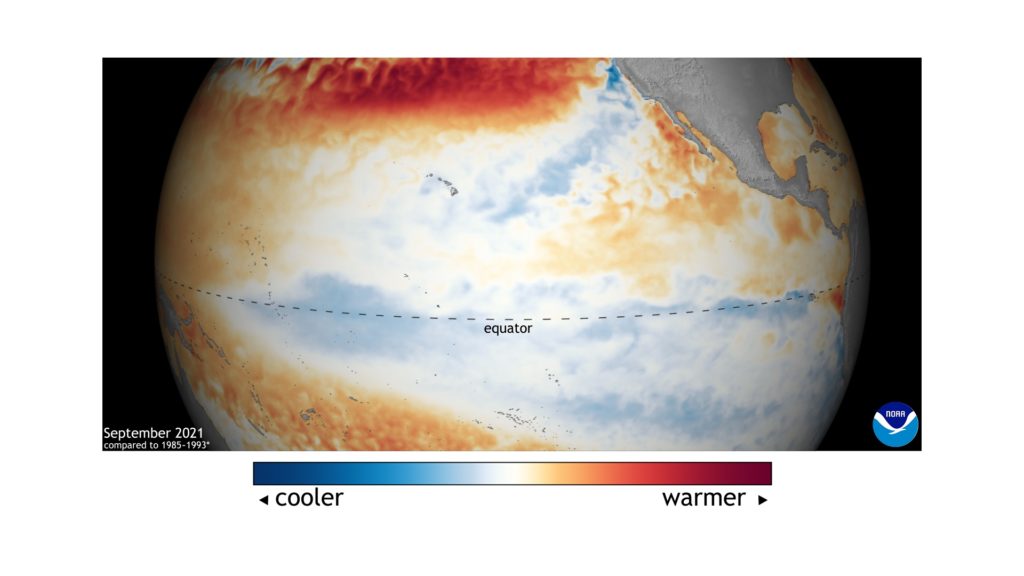

La Niña is one-half of a swing in atmospheric and oceanic conditions that occurs in the Eastern Pacific Ocean that is collectively called the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). In La Niña, the sea surface temperatures are at least 0.5 degrees Celsius colder than the long-term average, so this is called the cold phase. In the opposite warm phase, El Niño, the ocean water is at least 0.5 degrees Celsius warmer than the long-term average.

In between these two states is referred to as ENSO neutral. The swings occur in a semiregular pattern that lasts from two to seven years and is usually strongest in Northern Hemisphere winter. An El Niño seldom lasts for more than one year, but a La Niña can last for one or two years (and occasionally even three years). The winter of 2021–2022 is the second year of a La Niña event.

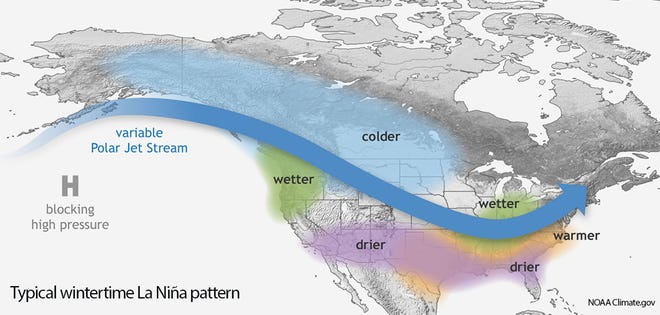

The cold water of a La Niña shifts the pattern of weather in the tropics and acts like putting a rock into the atmospheric flow of air that moves weather around the globe. In a La Niña winter, the flow of air (the jet stream) that pushes around storm systems in the subtropical regions is pushed north. That means clouds, rain, snow and cooler temperatures also shift north, leaving sunny skies and dry conditions in the southern United States.

WARMER WINTER LIKELY

Statistically, the southern United States is expected to be warmer and drier than usual in a La Niña winter because of the shift of the jet stream to the north (Figure 1). That means that in most La Niña winters, forecasters have a fairly good idea of what the climate will be like. In El Niño, the effects are the opposite, with cooler and wetter conditions in the southern states and warmer and drier than normal conditions in northern states.

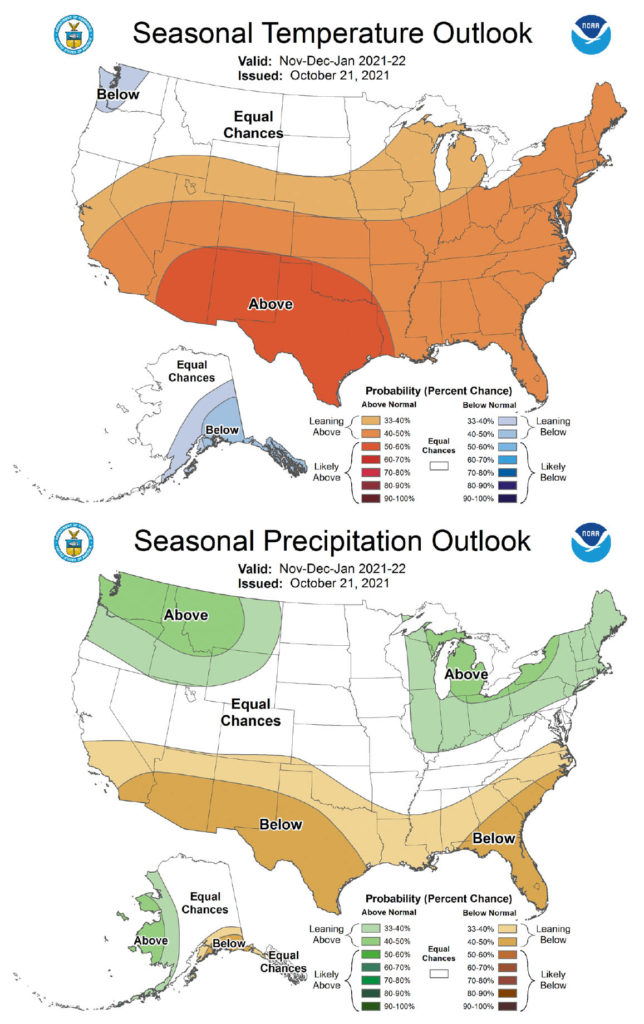

The Figure 2 maps show the predicted winter conditions based mainly on the presence of La Niña with a splash of impacts from long-term trends. By the time this article comes out, it will be known whether this forecast was accurate or not. Like any statistical relationship, it can occasionally be off by quite a bit.

In February 2021, an unusual and foreseen atmospheric event called a sudden stratospheric warming occurred that allowed a blast of frigid air to move south into the central United States and eventually all the way down to Texas and even into Mexico. This was a rare event that did not line up with the statistical forecasts of a warmer than average winter. But even with unusual events like these, most of the time forecasts based on the ENSO phase can provide useful information about what the winter climate is likely to be.

Because La Niña impacts local temperatures, it also has effects on related variables. In Wisconsin, where I lived for many years, La Niñas were associated with especially long ice-fishing seasons because the colder than normal air allowed lake ice to develop early in the winter and last for a long time.

GROWER CONCERNS

In the South, the warm and dry conditions in La Niña winters are related to a decrease in the number of chill hours needed for fruit crops like Georgia and South Carolina peaches and blueberries. This is a special concern as rising regional temperatures are already decreasing chill hours for many plants, and it is becoming harder for some crops to get enough cold to get good blossom development for spring fruit production.

If you are a fruit grower, by now you are probably watching your crops carefully to see how many chill hours they have accumulated over the winter. In the Southeast, chill hours can be viewed for an area at agroclimate.org/tools/chill-hours-calculator. Find maps for other parts of the country at mrcc.purdue.edu/VIP/indexChillHours.html.

Scientists do know that neither El Niño nor La Niña is prone to more frequent late frosts. In fact, frosts are more likely to occur in neutral years than in years on either end of the ENSO swing, especially in the South. So, if La Niña goes away quickly in 2022, a late frost is more likely to occur based on statistics.

Another concern in the South is that the drier and warmer conditions reduce the chance of soil moisture recharge that usually occurs in the cool and wet winter months, setting the stage for a possible drought in the summer following the La Niña winter conditions. It’s too early to say what will happen in summer 2022 at this point, but producers in the southern half of the country should be watching carefully to see how the winter conditions have affected the availability of soil moisture as the growing season begins.

Maps of archived climate information are available at hprcc.unl.edu/maps.php?map=ACISClimateMaps to see how accurate this year’s forecasts were.

Pam Knox is an agricultural climatologist at the University of Georgia J. Phil Campbell Sr. Research and Education Center in Watkinsville.