By Camila Rodrigues

The number of news stories on produce recalls from retail stores and outbreaks related to contaminated food have increased in recent years. These include recent cases of hepatitis A linked to fresh strawberries and several cases of E. coli outbreaks linked to romaine lettuce.

The terms “recall” and “outbreak” can be very confusing since they are commonly reported at the same time. They are usually issued by health officials including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). To clarify the differences between food recalls and foodborne outbreaks, producers need to understand why a product has been recalled or involved in an outbreak, so they can take actions to minimize negative impacts on their product sales and operations.

Health hazards can be introduced to food products at any point in the food supply chain. These include chemical (e.g., pesticides, sanitizers and cleaners), physical (e.g., metal, glass and plastic pieces), and biological (e.g., bacteria, virus and parasites) hazards. Allergens such as peanut, egg, milk, soy and shellfish are also considered health hazards that can cause life-threatening reactions and are commonly associated with food recalls.

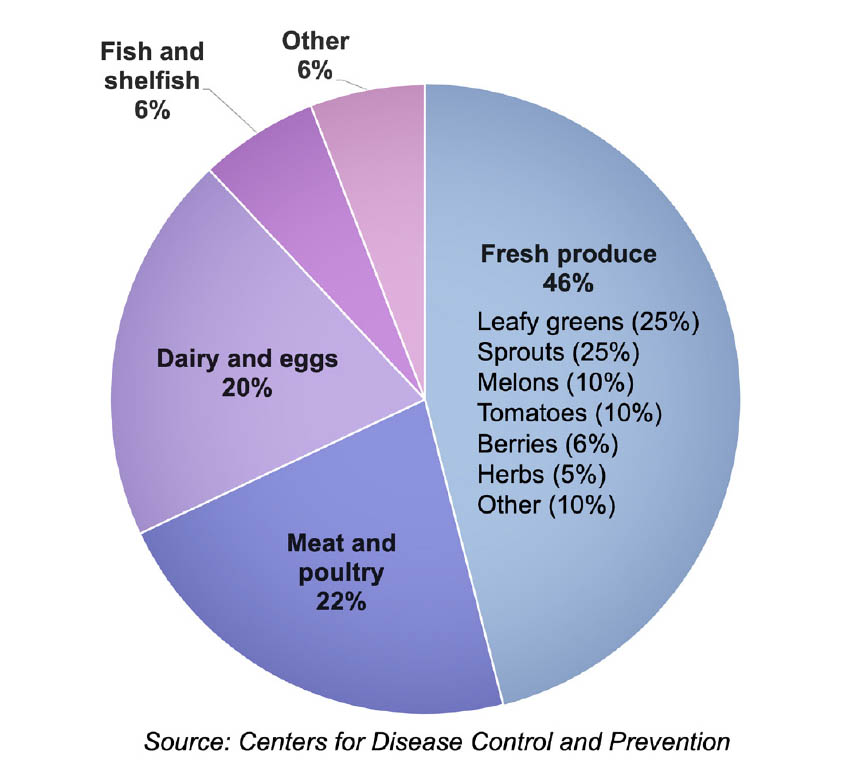

The major cause of foodborne outbreaks in the United States is Salmonella. Fresh produce is the No. 1 product of contamination, accounting for nearly half of foodborne outbreaks every year. The lack of an efficient “kill step” or decontamination process for fresh produce makes this commodity high-risk for foodborne illnesses. Food can become contaminated at any point in the food supply chain, from the farm to the consumer’s table.

UNDERSTANDING THE DIFFERENCES

Still, what is the difference between a recall and an outbreak? The answer is simple. Foodborne outbreaks occur when two or more people get sick from the same contaminated food or beverage. A food recall is the removal of contaminated products from the market because of a health-hazard risk.

However, it is not true that all outbreaks will lead to recalls, or all recalls will lead to foodborne outbreaks. Circumstances can be very specific depending on each situation. In most cases, a foodborne outbreak is followed by a product recall, but the opposite may not be true. Sometimes, the source of a foodborne outbreak is only identified after a product has been expired and removed from the shelves. Consequently, it does not require a recall. Some recalls might happen before the product is available to consumers, if authorities can identify the contamination prior to the outbreak occurring. In a lot of other cases, a product recall is not issued because the source of the outbreak has never been identified, which could lead to more illnesses.

Typically, when an outbreak is identified, an investigation is quickly initiated by public health agencies, including state health departments, the FDA and the CDC. They will collect as much information as possible to determine the source of the outbreak and prevent more future illnesses. During the investigation, these agencies issue an investigation notice to warn people of an ongoing foodborne outbreak not yet linked to a food source. Once the source and origin have been identified, health authorities issue a public health alert to provide urgent and specific advice with details about the name of the product and specific lot numbers.

GROWER ADVICE

So, when should growers be concerned? When a public health alert is issued for an ongoing outbreak and the source of contamination has been identified, growers should be prepared for the negative impacts on their sales for that specific product that is involved in the outbreak.

For example, romaine lettuce sales have significantly dropped in the past five years due to consecutive outbreaks, representing millions of dollars in lost sales. This directly impacts growers in every state because consumers will not likely switch to alternative brands or look for the origin of the product. Instead, they will just temporarily stop buying that specific food. Then, when the outbreak is resolved, sales are unlikely to immediately recover. In this case, growers need to find solutions to remediate the problem and find other marketing options to minimize their losses.

If a grower’s food has been associated with a foodborne outbreak or a recall, the best solution is to act immediately to avoid more losses and illnesses. Implementing food-safety practices and monitoring programs is crucial to minimize risks that could lead to a recall or even a foodborne outbreak. The costs associated with a recall can be hundreds of times more than the costs of implementing new food-safety practices.

Recordkeeping is essential on a farm. Not only does recordkeeping help to make good decisions in terms of corrective actions but also to provide valuable information in the event of an outbreak associated with a farm’s food.

Growers should keep in mind that fresh produce is a high-risk food. Just because one product has never been associated with an outbreak before doesn’t mean that the risks of contamination are low and preventive measures are less important. The key to reducing foodborne outbreaks and food recalls is prevention. Thus, implementation of food-safety practices and following regulatory requirements and industry guidelines are crucial steps to reducing risks.

The FDA and the CDC maintain an updated list of the outbreak and adverse event investigations, so people can be aware of the current information related to foodborne outbreaks and/or food recalls. For more information, see the following websites:

- fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/investigations-foodborne-illness-outbreaks

- cdc.gov/foodsafety/outbreaks/multistate-outbreaks/outbreaks-list.html

Camila Rodrigues is an assistant professor and food safety Extension specialist at Auburn University in Alabama.