By Frank Giles

This past summer, the Biden administration released a proposed rule from the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) to protect indoor and outdoor workers from excessive heat. The proposed rule would require employers to develop an injury and illness prevention plan to control heat hazards in workplaces affected by excessive heat. Among other things, the plan would require employers to evaluate heat risks and — when heat increases risks to workers — implement requirements for drinking water and rest breaks. It would also require a plan to protect new or returning workers unaccustomed to working in high-heat conditions.

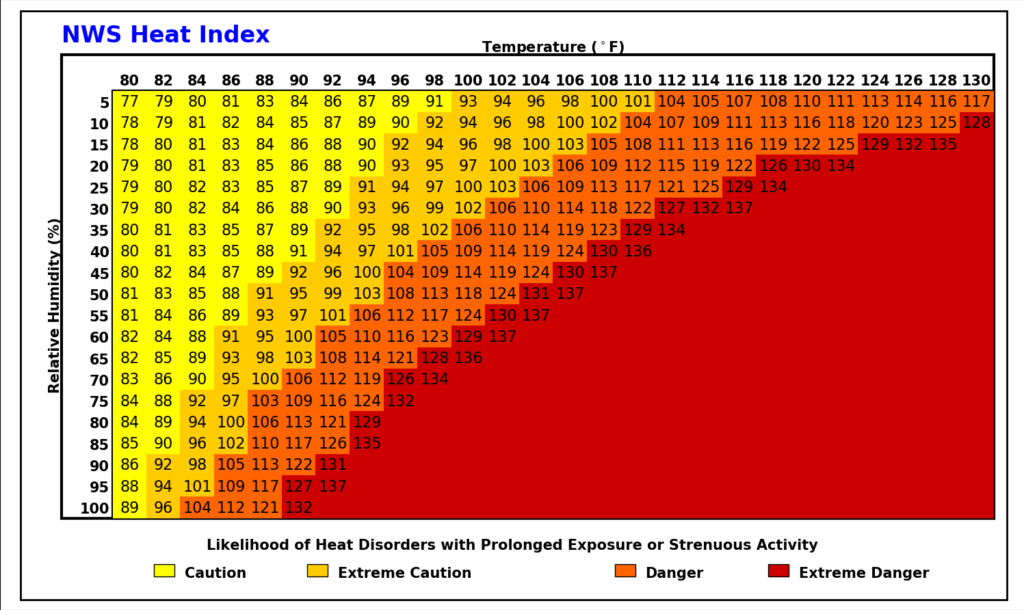

The rule would set an “initial heat trigger” at a heat index of 80 degrees, at which employers must provide drinking water and break areas. It would set a “high heat trigger” at 90 degrees, requiring employers to monitor for signs of heat illness and provide mandatory 15-minute breaks every two hours.

Rule Fate Uncertain

In December, the DOL extended the public comment period for the proposed rule until Jan. 14. The outcome of the rule is uncertain given the Trump administration takes control of the White House in January.

Regardless of federal regulations, there have been attempts at the local level to require worker-protection plans for heat. Some farm groups are recommending that growers create a heat management plan and training to protect their business and their workers, because this will be an ongoing regulatory issue.

Last year, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences released guidance on how to build such a plan for farms and other businesses. The document, Building Blocks for a Heat Stress Prevention Training Program, is available at is.gd/HEATPLAN.

During the winter months, it is a good time to develop a plan for training employees to recognize and mitigate heat stress.

Know the Signs

When a worker is beginning to experience overexposure to heat, there are signs employees should be trained to know.

Heat Cramps: These symptoms manifest as muscle pain and spasms in the abdomen, arms and legs. If this occurs, the person should stop what he or she is doing and move to a shady, cooler spot. Drink water with a bit of salt or a sports drink (especially if the person has not eaten anything containing salt lately).

Heat Exhaustion: As heat stress progresses, symptoms expand to dizziness, headaches, nausea and unsteadiness. The person should be moved immediately to a cool place away from potential chemical exposure. If wearing personal protective equipment (PPE), that should be removed to reduce heat burden. Drink up to 64 ounces of water in an hour. If the person’s condition doesn’t improve or worsens within the next 30 minutes, seek medical attention.

Heat Stroke: The condition now is a medical emergency with symptoms that include convulsions, chills, vomiting, mumbling of speech, combative behavior and passing out. In this situation, cool the person and call emergency services immediately. Remove excess clothing and cool rapidly by putting the person in an ice bath. Continue cooling the person while waiting on emergency services.

Preventive Measures

Prevention is the best medicine for heat stress. One key element is staying hydrated, which can sometimes be difficult even for someone trying to accomplish the task. The key is to drink water before, during and after work. One cup of cool water every 20 minutes is recommended, even if the person is not thirsty. For longer jobs, drinks with electrolytes (sports drinks) are recommended. Avoid energy drinks and alcohol.

When taking breaks, find a shady, cool spot to allow the body to recover. Dress for the job. Light-colored, loose-fitting clothing is best, topped off with a hat to provide shade.

Employers, crew leaders and employees should know the risk factors posed by heat and understand that not everyone reacts in the same way. So, all these mitigation efforts should be considered at the individual level. That means observing and communicating how well people are reacting to the heat. And understand that people wearing PPE are at heightened risk for heat stress.

Helpful Checklist

The document provides a checklist to help ensure a heat-stress management program is in place and being followed. One of the first factors is determining how hot it will be during the working hours. Heat plus humidity increases the potential for risks. That’s important in the hot and humid Southeast.

Other checkpoints include monitoring worker hydration and scheduling breaks to ensure everyone has time to cool down. Guidance also suggests the creation of a buddy system where co-workers team up to monitor hydration and potential heat stress.

While much of what is suggested in the guidance from the institute seems like common sense, if it is not written down and part of employee training, it could get overlooked in the rush of the busy planting and harvesting seasons. Having a formal plan in place will protect the farm and the farmworker.