Photo by Frank Giles

By Frank Giles

In 1928, three young brothers began selling produce off a pushcart on the streets of Boston. That was the beginning of DiMare Company, a family business that has now spanned generations and has grown into diversified farming operations. The company is one of the largest field grown tomato producers and packers in the United States.

“We are in our 96th year as a company. My grandfather Anthony DiMare, who I am named after, and his two brothers Joseph and Dominick started it all with a pushcart on the streets of Boston,” says Tony DiMare, president of DiMare Fresh and DiMare Homestead. “They were young teenage kids selling produce. They soon were making money and had grown the business such that they wanted to buy a building and expand. Being teenagers, they were too young to qualify to get a loan, but the president of the local bank where they were depositing their earnings had taken note of these young boys’ work ethic. He personally guaranteed and co-signed for the loan to help them buy the building, and the rest is history.”

Photo courtesy of DiMare Company

By 1930, the brothers had grown into a wholesale and repacking business with their building near the Boston Terminal Market. They were moving large volumes of tomatoes, other fruits and vegetables, nuts and dates. By 1939, the company became a year-round supplier of tomatoes through relationships with farmers in Florida and California.

Family Begins Farming

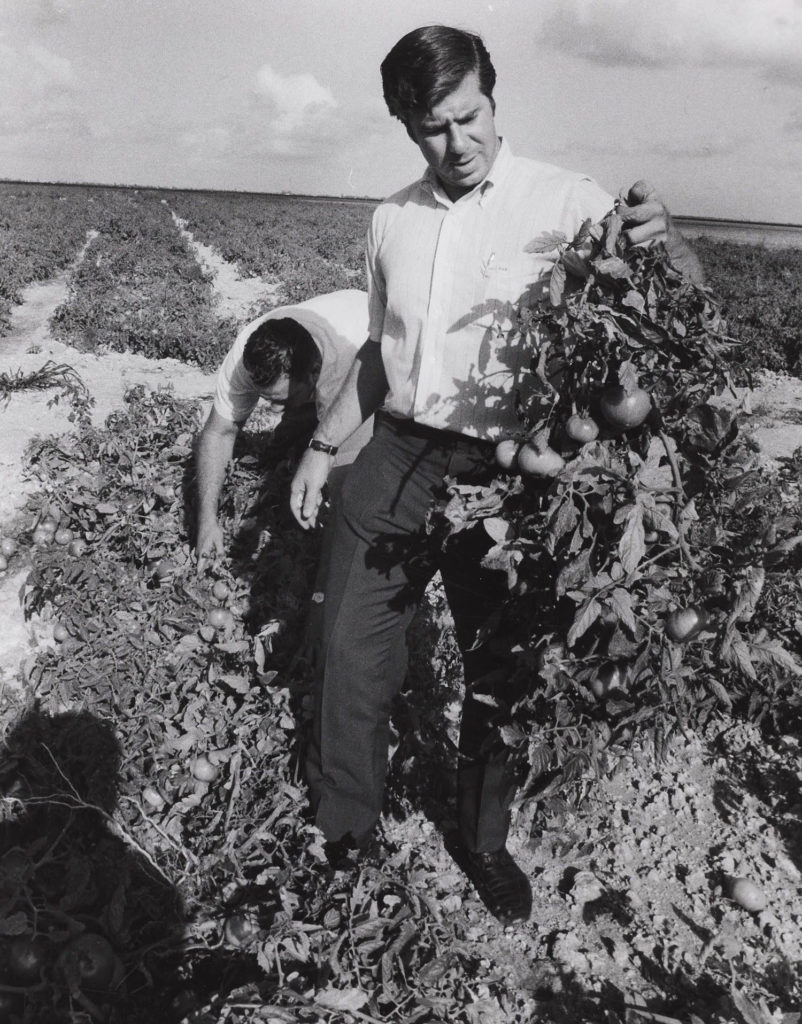

In the late 1940s, the DiMare family got into the farming side of the business in the Fort Pierce area. Joseph came down to start the farming operations. Eventually, his son Jim would join his father on the farm after he finished college. Then in the early 1950s, Dominick started a farming operation in California. The family even sourced tomatoes out of Cuba prior to Castro’s takeover, with Dominick spending time in the winter in Cuba buying produce for the company back in Boston.

“That was how we got involved in the farming side of the business,” DiMare says. “The family was looking for security of supply and felt getting directly involved in farming in Florida and California would help achieve a reliable high-quality supply of tomatoes. My dad Paul DiMare came to Florida in the mid-1960s and purchased a packing cooperative operation (Southmost) in the Homestead area, which would become Florida Tomato Packers and eventually, DiMare Homestead.”

In the coming years, growing and packing operations were started in the Immokalee, Palmetto and Ruskin areas. In the mid-1970s Paul bought out Tommy Campbell, who he had partnered with at Stonoca Farms in John’s Island, South Carolina, which would become DiMare Johns Island. The DiMare-Ruskin packing facility, which was formerly Stake Tomatoes of Ruskin, was purchased in 1989.

Growing the Business

The DiMare work ethic was passed down through the generations, and the company saw continued growth and diversification. Today, the business includes farming, wholesale programs, foodservice distribution, f loral processing, warehousing and distribution, and value-added services for retail customers.

“If it wasn’t for the interest and desire of each generation to want to work in the family business, the company would have never reached this point,” DiMare says. “We are four generations deep, with second, third and fourth generations active in the company today. The family is directly involved in all phases of the business from overseeing and managing our farming operations, managing packing operations, handling company sales and managing repacking and distribution operations (DiMare Fresh.) In addition to family, we have been very fortunate to have numerous longtime employees that have worked for the DiMare Company for numerous years, some for decades. Without a doubt, the company could not have persevered without the many dedicated and loyal employees over our nine decades. We are very fortunate and blessed to have so many great employees.”

Tomato Market Dumping

According to DiMare, the company’s diversification over the years made good business sense, but also was necessary to survive in a market distorted by ever-increasing imports of tomatoes, especially from Mexico. Ever since the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into force in 1994, the domestic tomato market has been upended by a flood of tomatoes from the country.

“If you go back to pre-NAFTA, Florida was more than two-thirds of the winter supply of tomatoes, and Mexico was only a third. Today, that has completely flipped where we are around 30% of supply in the wintertime and Mexico commands the rest,” DiMare says. “I made a comment to the blue berry guys back some years ago to be prepared, because when Mexico starts growing a commodity, they don’t do it in a small way, and it will only be a matter of time before you will see rapid growth and surges of volume pouring into the U.S. marketplace. And, of course, bell peppers, cucumbers, squash and strawberry growers all have felt the wrath of Mexico and the surges of volume, that in some cases have destroyed markets and forced growers out of business.”

“Foreign producers grow primarily for export to the U.S. market. That is not going to change unless we drastically change our trade policy,” DiMare says. “The problem is specialty crop agriculture is such a small part of the overall trade policy picture that our priorities are overshadowed. That doesn’t mean we won’t continue to fight for fair trade and an equal playing field. That fight is never going to end. Free trade agreements are supposed to be fair and equitable. I argue that NAFTA and now the USMCA (United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement) have not been fair or equitable.”

Photo courtesy of DiMare Company

There have been efforts to protect the U.S. tomato producers from injurious effects from Mexican producers through multiple suspension agreements with Mexico (see more on page 30). But the agreements have not helped Florida and Southeastern tomato growers, or tomato growers across the country for that matter. The Florida tomato industry has asked the U.S. Department of Commerce to terminate the latest agreement, because of its failure to eliminate the injury caused by dumped tomatoes (tomatoes sold for less than the established minimum reference price of the Tomato Suspension Agreement) from Mexico. DiMare said he doesn’t believe much will happen on the trade front before the November election.

“The current agreement will sunset this summer at the end of August. At this time, there will be negotiations on whether the agreement will be renewed or possibly terminated,” says DiMare. “I think if there’s a change in the administration, there may be an opportunity to address it and for us to express our dismay that these agreements have never effectively worked in their almost 30 years of existence. It actually has been a detriment to the domestic industry. That’s because there really is no effective way the Department of Commerce can enforce it.”

Staying Involved

DiMare says being involved on the policy front is crucial, despite the challenges the specialty crop industry faces going up against larger interests that might have more sway on the political front. He’s been a longtime member of the Florida Fruit & Vegetable Association (FFVA). He has served as chairman of the association and says the organization swings above its weight class in serving the industry. He also served as chairman of the Florida Specialty Crop Foundation for 13 years.

“From a member standpoint, FFVA does it as good as any association in the country. And they stay on course and do not waver from special interests. At every level, whether it is labor, environ mental, trade issues and more, they are top-notch,” DiMare says.

There’s no shortage of issues impacting the industry. Beyond trade, specialty crop growers are still dealing with significant inflation to input costs and squeezed margins for the produce they grow and pack. And new changes to the H-2A program are making that critical program more expensive and difficult to use than ever. DiMare says the undercurrent of recent bankruptcies in the food sector and elsewhere should be a warning signal the economy is heading in the wrong direction.

“It is very expensive to operate a business today,” DiMare says. “Because of the supply and demand nature of our business, we don’t have the ability to add on the increased costs to our goods, so the increased costs just continue to shrink margins. Scale is all relative.”

But despite the challenges, DiMare says there’s nothing else he and his family would rather be doing.

“What we love the most about growing, packing and shipping of our products is knowing that we play a part in the fresh produce supply chain and feeding the public nutritious and healthy fresh fruits and vegetables,” he says. “Our family has always been known as leaders in the industry, renowned for our innovative ideas, advancement in technology and for the quality of our products that we produce and pack. We take great pride with all that we do in all our operations and are proud to promote the DiMare name on our products.”