By Frank Giles

Specialty crop farms across the Southeast have faced myriad challenges over the past few decades, but many farms have embraced new market opportunities and enjoyed growth. One of those operations is L&M. The farm was founded in 1964 by Joe McGee in Johnston County, North Carolina.

In the years since its founding, L&M has grown into a large producer of brassica crops like broccoli and cabbage in Florida and South Georgia. The farm also produces potatoes, squash and peppers as core crops. L&M produces 35 different types of crops based on market demands. Florida and Georgia locations include about 7,000 acres.

Adam Lytch manages farming operations for L&M. He has been with the company for 18 years.

“When I was in school at North Carolina State University, I met someone from L&M and developed a relationship with him and got to know the McGee family. I joined the company after I graduated. It is the only job I’ve ever had outside of working on my own family row crop farm.

Partner Growers

“I started working out of L&M headquarters in Raleigh, North Carolina, but gravitated toward the growing side of the business. I was traveling down to Georgia and Florida a lot to help with farming operations. Then, about eight years ago, I moved to Florida full time. Today, I oversee our farming and warehouse operations and manage the relationships we have with outside growers.”

In the East Palatka, Florida, area, L&M has six partner farms that grow under the L&M labels and brands. L&M grows roughly 60% of the product in the area, and partner farms make up the rest.

“We work these family farms into our planting schedules,” Lytch says. “It helps us because we are diversifying into different growing areas rather than having all our eggs in one basket growing in one location. The outside growing partners are an invaluable part of our program.

“We help provide the partner growers with plants and seed and the labor for harvesting. They get the benefit of being part of a regional business, but also a national brand and the distribution that we provide. It is a win-win for us and the partners. Those relationships range from 5 to 40 years old.”

L&M markets its brands to major retailers. Lytch says that is partly due to the crop mix produced on the farm.

“There are some things like cabbage and potatoes, where we have some pack styles that lend themselves to food service, but predominantly we are retail. Every retailer in the Southeast, we are supplying at least something to,” he says. “We work with some of them on year-long commitments that we must source outside of our Florida and Georgia production. And for some, we have purely local and regional in-season programs. Those are really important to us.”

Variety Trialing

L&M was built around its brassica business. There is a constant search for improved varieties and production practices to keep the quality bar high.

“Cabbage was the first major crop that L&M planted in Florida. That was close to 50 years ago,” Lytch says. “It has always been a core item. Broccoli is also big for us, and we’ve been doing that for 22 years. It is a segment that has grown the most because East Coast broccoli has taken hold more in the past decade. We have better varieties now bred for our climate and conditions. Broccoli was originally bred for the West Coast and drier climates.

“The challenges were growing in our wetter climate and the shorter season. Another challenge was competing against California … So, we not only had to produce equal quality, but we also had to have better quality to break into that market. We have good broccoli varieties now and can do a really nice job on quality.”

Lytch says the search is ongoing for new and improved varieties for all crops grown on the farm.

“We work with all the major seed companies trialing new varieties that they have in development. We probably have between 80 and 100 trial varieties planted on the farm right now,” he says. “The varieties we change over time, but a lot of them are slotted. We know there is a variety that works well planted in the month of September, so we keep that variety in that slot. Broccoli, where we have a 20-week production window, we cover with several different varieties. Plus, we like to overlap varieties in case something goes wrong with one of them. We need to keep diversity there.”

When trialing new varieties, Lytch says they like to see a variety do well for at least a couple seasons. Then they might go on to larger-scale plantings based on demand.

“For instance, you look at red cabbage. The varieties are not as well refined. It is pretty cabbage, but it is going to be hard to beat the varieties we already have. And we’ve got them really dialed into the windows we need to plant them in. We understand what to do when something goes haywire with them. So those red cabbage varieties are going to be hard to replace.

But, if we see something promising in a variety where we need something either for production or demand from our buyers, we’ll put something in on a larger scale. Sometimes it works and sometimes it does not. That is why we do the level of trials that are conducted on the farm. And we can provide constructive feedback to the seed breeders about what we need.”

Pest Problem

Diamondback moth is the major pest concern in brassica production on the farm, especially in late-spring cabbage in Florida.

“The diamondback can be nasty at times, particularly after an extended dry season where we are not getting our regular seasonal rains to help break the cycle,” Lytch says. “The life cycles reproduce so fast when they do come in, so it is so important that you stay ahead of them with your scouting program. The key is catching them early and not letting them get established.”

Staying Competitive

Lytch says keeping on top of customer and consumer demand is now more important than ever. Consumer tastes in produce items can move more freely and quickly now in the information age where online influences can create changing demand. That must be balanced with economic production realities on the farm.

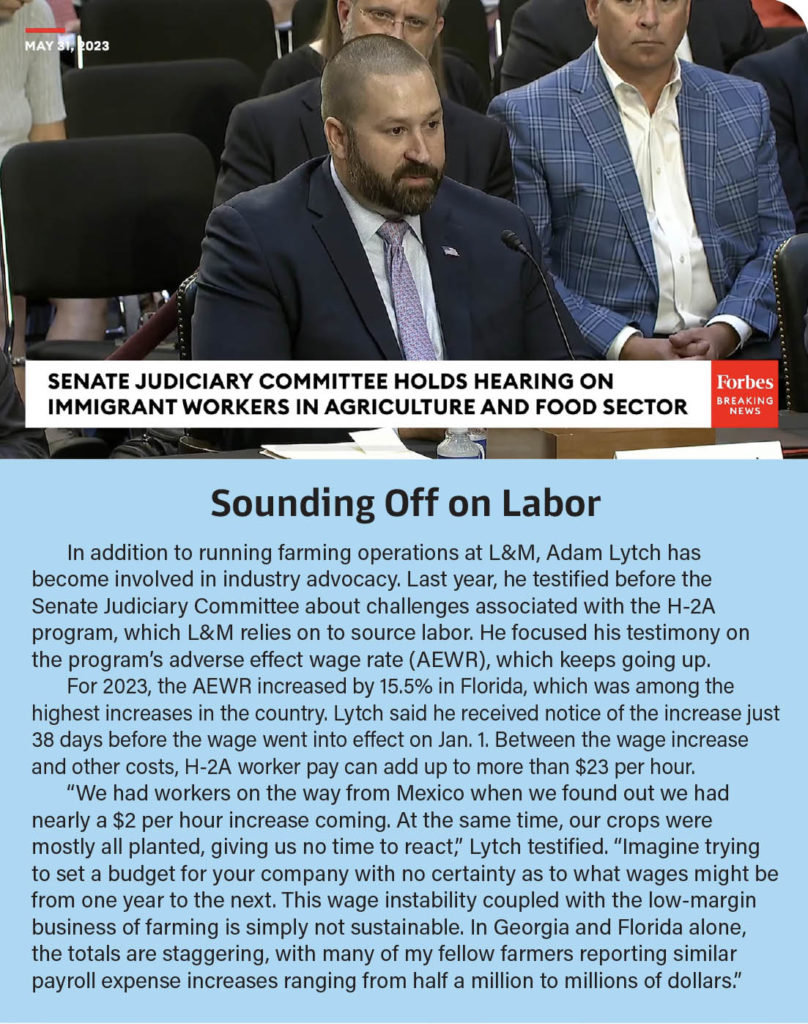

“We must continue to invest in and find labor-saving technology. That is the only chance in maintaining the diversity of specialty crops we produce now in this country,” Lytch says “The ones that are less labor intensive are as strong as ever. The crops that are very labor intensive, in five years without some serious technology implementation, it will change the types of crops we are growing. Sadly, those crops will just be imported.

“But I am very optimistic that technology is coming that fast. It sounds cliché, but we have to take every opportunity we have to keep educating people about the importance of supporting U.S. agriculture. We have a growing population in the Southeast. The good news for us is there are more customers closer to our farms than there ever has been. We are growing healthy crops and can promote that the more you consume of our product, the healthier you are. We just need to maintain an environment where growers can remain profitable in growing those items.”