By Clint Thompson

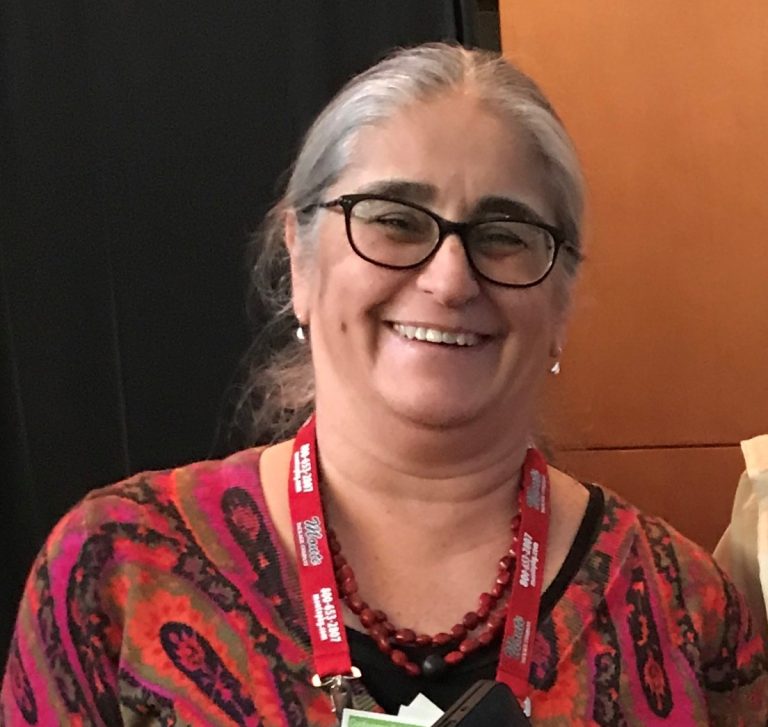

The future of strawberry production in North Carolina lies in Gina Fernandez’s research lab at North Carolina (N.C.) State University. The strawberry breeder is responsible for developing the newest strawberry variety adaptable to the state’s environment.

“California has beautiful climate, nice day length and temperatures, cool temperatures that strawberries like to grow in. Florida has a breeding program where strawberries do not need a chilling requirement, so that means that they do not need to go through a winter dormancy period,” Fernandez said. “Our genetics are not necessarily the same as either one of those. We need to develop something in this region that has a climate that is similar to what would be adapted here.”

She discussed strawberry breeding during the Southeast (SE) Strawberry Expo, held Nov. 9-11 in Asheville, North Carolina (N.C.)

“The breeding program in North Carolina exists because we are not California, and we are not Florida. We have a different environment, so we like to develop some varieties that are adapted to North Carolina and surrounding states,” said Fernandez, a professor in horticultural science at N.C. State.

North Carolina strawberry growers have used California-bred strawberries for years, including Chandler and Camarosa. However, the region needs its own strawberry variety, so growers can take production to the next level.

Fernandez said developing traits such as good flavor and disease resistance top her research agenda. She also wants strawberries that are shippable, those that are not as firm as ones developed in California.

“We feel like we’re getting a good handle on disease resistance and flavor and hoping that in the next few years we will be able to release some of those cultivars that have those traits. It’s hard to get flavor, firmness, yield and disease resistance all in one cultivar,” Fernandez said. “That’s where we have these different pipelines out there to try to concentrate those traits. Then we’ll use one of those cultivars with a concentrated trait with another that has good flavor and disease resistance. We hope those progenies will have the combination of traits more frequently than you would with just a random cross.”

She noted the disease that concerns her and growers the most is anthracnose, which can affect the plant’s fruit, flowers, crowns, leaves, petioles and roots. Its impact speaks to the importance of Fernandez developing disease resistance traits in a region where strawberries are prone to multiple diseases.

“If it tastes pretty good and has a whole mess of diseases in North Carolina and Southeast United States, that will completely wipe out that crop. It can be a fruit disease, crown disease, leaf disease; multiple diseases that can potentially impact the yield of that strawberry,” Fernandez said.

Fernandez said it usually requires 10 to 12 years of research to develop a strawberry variety. She expects the next cultivar to be released in 3 to 4 years.