By Juan Carlos Díaz-Pérez

Vidalia onions are sweet, short-day, low-pungency, yellow Granex-type bulbs popular in the United States because of their mild flavor. These onions are exclusively grown in southeastern Georgia, in a region with mild winters and low-sulfur soils. There is increasing interest in utilizing organic fertilizers because of the growing demand for organic vegetables, including organic sweet onions. There is, however, limited information about the application rates of organic fertilizers to vegetable crops in Georgia.

Most fertilizer recommendations were established for vegetable crops grown using chemical fertilizers. There is precise and ready nutrient availability when using chemical fertilizers. By contrast, soil nutrient release and availability, including that of nitrogen, are complex with organic fertilizers. Thus, when organic fertilizers are applied, there is always the uncertainty of how much nutrients will be available to the crop. In contrast, if 50 pounds of nitrogen per acre are applied as chemical fertilizer, there is certainty that amount will be readily available to plants.

RIGHT NITROGEN RATE

Nitrogen concentration and release rates vary among organic fertilizers. Insufficient soil nitrogen availability is frequent in organic vegetable production because the release of nitrogen from the organic fertilizer is not in synchrony with the crop nitrogen uptake. Manufacturers of organic fertilizers are now starting to include information about the nutrient release rates of fertilizer.

Traditionally, the goal of nitrogen management has been to maximize yields and economic return. Fertilizer management should look for a balance between profit, crop yield and environmental impact. The most used practice to determine the amount of organic fertilizer to apply is to consider the nitrogen content of the organic fertilizer and the crop nitrogen needs.

Nitrogen in fertilizer may be in inorganic or organic forms. The inorganic nitrogen (nitrate or ammonia) is readily available to plants. This nitrogen form is found in chemical fertilizers (ammonium sulfate, ammonium nitrate, calcium nitrate, urea, etc.). The availability of nitrogen may vary depending on the type of organic fertilizer and the environmental conditions. The organic nitrogen form is not readily available to plants and requires mineralization, a “digestion” process conducted by soil bacteria. During mineralization, soil bacteria transform organic nitrogen into ammoniacal nitrogen through enzymatic reactions. Nitrogen mineralization increases with temperature and varies depending on the bacterial population densities.

TRIAL RESULTS

Studies were conducted in Tifton, Georgia, to evaluate the effects of organic fertilization rates on sweet onion plant growth. An organic fertilizer [microSTART60 (3-2-3), Perdue AgriRecycle, LLC] was produced from chicken litter and was applied before planting the onions. No more fertilizer was provided after planting.

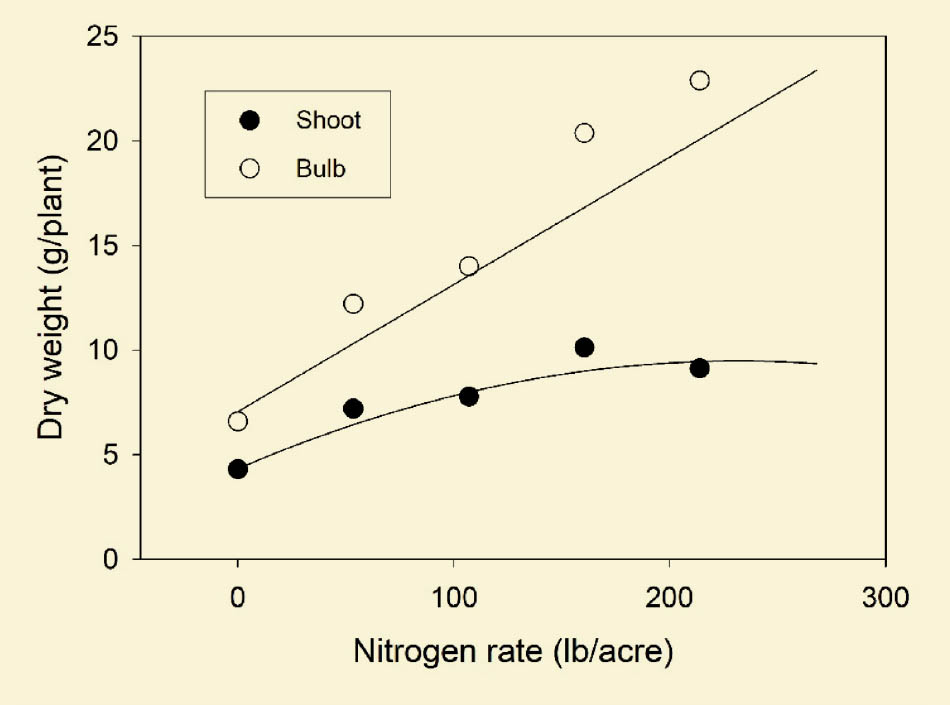

Results showed that onion shoot growth increased with greater organic fertilizer rates because of augmented soil nitrogen levels (Figure 1). Shoots showed nutrient deficiencies late in the season, even at high organic fertilization rates (Figure 2). These nutrient deficiencies indicate that preplant application of organic fertilizer was sufficient to cover plant nutritional needs partially, and that organic fertilizer applications may be necessary later in the season.

High application rates of organic fertilizer (above those required by the crop) may have resulted in significant nitrogen leaching. It is unlikely that the onion crop used most of the mineralized nitrogen. Nitrate leaching is common after heavy rains or high irrigation rates, particularly in light soils, like the sandy loam soil of this study.

Researchers could not determine the optimal organic fertilization rate for maximal bulb growth. Bulb dry weight climbed with increasing organic fertilization rates, with the curve never reaching a maximal point. These results indicated that even at the highest organic fertilization rate (214 pounds per acre of nitrogen), onion plants were deficient in nitrogen and other nutrients. Supplemental fertilizer applications at the bulb enlargement stage may be necessary.

Acknowledgment: This report is based on the journal article in HortScience Volume 53, Issue 4 (see doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI12791-17).

Juan Carlos Díaz-Pérez is a professor at the University of Georgia in Tifton.