By Johan Desaeger

Producing nematode-free plant material is one of the most important steps in nematode management. Many nematodes can hide in plant material such as tubers, bulbs, roots, cuttings and seed.

The seed gall nematode (Anguina tritici), a seedborne pest infecting seed heads in wheat and rye, was the first plant-parasitic nematode ever to be described (by Needham in 1743). This nematode causes seeds to turn into easily recognizable galls which is why, with few exceptions, it has been very successfully eliminated through seed sanitation. Nematodes that hide in soil, roots, rhizomes and other plant material, however, are much more cryptic and usually do not show any obvious damage symptoms. This means that they can easily and unknowingly be spread via tubers, bulbs and bare-rooted or plug transplants.

CLEAN PLANTS ARE KEY

Avoiding the introduction of nematodes in agricultural fields should always be the first thing to consider when thinking about nematode management. Once nematodes become established, eradication is near to impossible or at best will come at a high price. Any effective and sustainable nematode management program must therefore start with the employment of nematode-free planting materials.

Heat treatment, known as thermotherapy, has been used at least since the 1930s as a cheap, non-chemical and environmentally friendly method for plant disease management through hot water, air and vapor. Hot water is successfully used in many crops throughout the world to help control nematodes in planting material such as apple, peach, cherry, citrus and grapevine rootstocks, onion sets, garlic cloves, flower bulbs and tubers, banana corms, ginger and hop rhizomes, and rice seeds. Many different types of equipment have been developed; temperature requirements and exposure times can vary significantly depending on the target nematode, type of plant material and crop species.

I will briefly discuss the potential of thermotherapy for one of the highest-value crops in Florida, strawberry. Most strawberry fields in Florida are fumigated before planting in order to reduce weed, disease and nematode pressure. While fumigation will help to control resident nematode populations (mostly root-knot and sting nematodes), pre-plant soil fumigation will not protect against nematodes that are introduced with planting material.

By the time of planting, the fumigant should have pretty much completely dissipated from the soil and will no longer provide any protection against nematodes or pathogens that come in afterward. In fact, the biological vacuum created by soil fumigation may provide a perfect habitat for such introduced nematodes to proliferate, with few or no competing or antagonistic organisms present. Regardless of fumigation or other treatments, using nematode-free plant material should always be a priority for any grower.

Strawberry is grown on about 10,000 acres in Florida, mostly in Hillsborough County. Over 100 million strawberry transplants (mostly bare-rooted) are brought in from northern nurseries in the United States and Canada every year. Foliar nematodes (Aphelenchoides besseyi), root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne hapla) and lesion nematodes (Pratylenchus penetrans) have all been found on these plants in recent years. The same is true for many damaging pathogens. This is why researchers at the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Gulf Coast Research and Education Center (UF/IFAS GCREC) started experimenting with the use of aerated steam to eliminate such pathogens and nematodes from bare-rooted strawberry transplants.

STRAWBERRY RESEARCH RESULTS

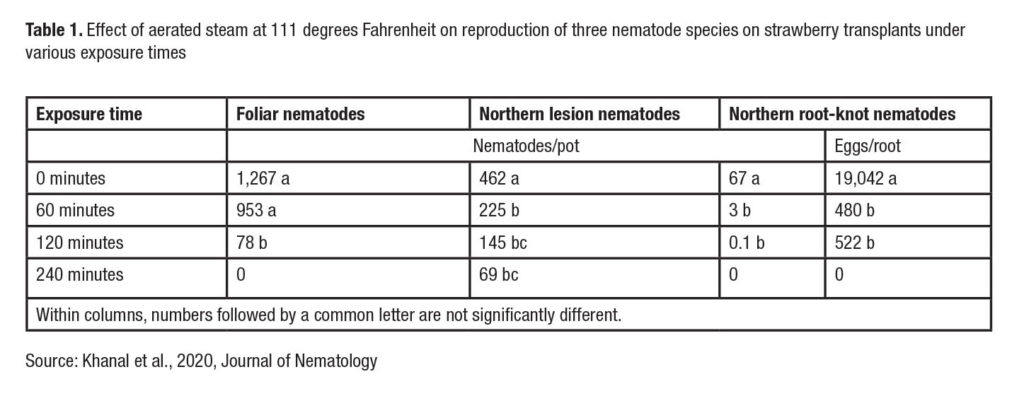

Natalia Peres, GCREC professor, has found the use of aerated steam treatments to be highly effective in ridding plants of hidden pathogens and nematodes. In artificially inoculated experiments using all three cryptic nematodes that have been detected on strawberry transplants in the past five years, good to excellent control, depending on the type of nematode, was achieved with aerated steam (Table 1).

Root-knot and foliar nematodes were the most sensitive and were completely eradicated after steaming at 111 degrees Fahrenheit for four hours. Lesion nematodes proved to be tougher and were only reduced by 85% following the same treatment.

Steam treatments had minimal or no adverse effect on plant growth, indicating that they could be a useful future tool to help manage nematodes in strawberry transplants. As of now, no commercial application is available for steaming of strawberry or other transplants. Considering the high number of plants coming into Florida each year, and the fact that plants are packed in cardboard boxes, significant scaling up and additional adjustments will have to be made before this can become an actual practice.

In the meantime, additional research into the use of aerated steam and other thermotherapy options, such as hot water, should be encouraged both in determining optimal treatment procedures as well as toward adoption efforts.

Johan Desaeger is an assistant professor at the UF/IFAS GCREC in Wimauma.