Word of a new Best Management Practices (BMP)

manual and regulations being released this year has been causing a buzz among Florida citrus growers. The reason: phosphorus. With the passage of Senate Bill (SB) 712 (

Clean Waterways Act) last year, Florida embarked on a legislative and regulatory path to address water quality issues plaguing sensitive ecosystems in the state, including those surrounded by homes on the highly populated urban coasts. Those coasts account for a lot of voters, and the promised action on water quality played a big role in the election of Gov. Ron DeSantis and Agriculture Commissioner Nikki Fried. SB 712 was the culmination of many of their election promises. While all parties agree action is needed to address water quality, there are concerns about phosphorus guidance coming from the

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS), the agency charged with administering the BMP program. Its Office of Agricultural Water Policy (OAWP) is the division overseeing the program. The new law mandates that FDACS inspectors visit farms at least once every two years to verify growers are following BMP guidelines. The law also requires growers to maintain records of soil and tissue analysis and fertilizer applications for verification purposes. Those inspections have been ongoing now for several months. According to FDACS, that’s when the phosphorus issue began to show up.

With fertilizer and fertigation practices changing so drastically since HLB became endemic, growers contend new research in plant nutrition, including phosphorus, is needed to reflect current, real-world conditions.

Photo by Frank Giles

How High Is Too High?

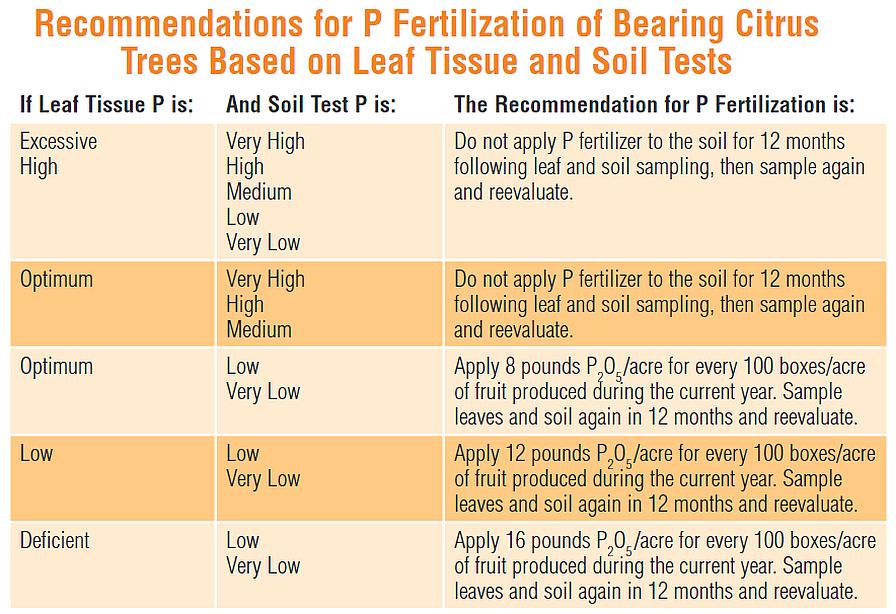

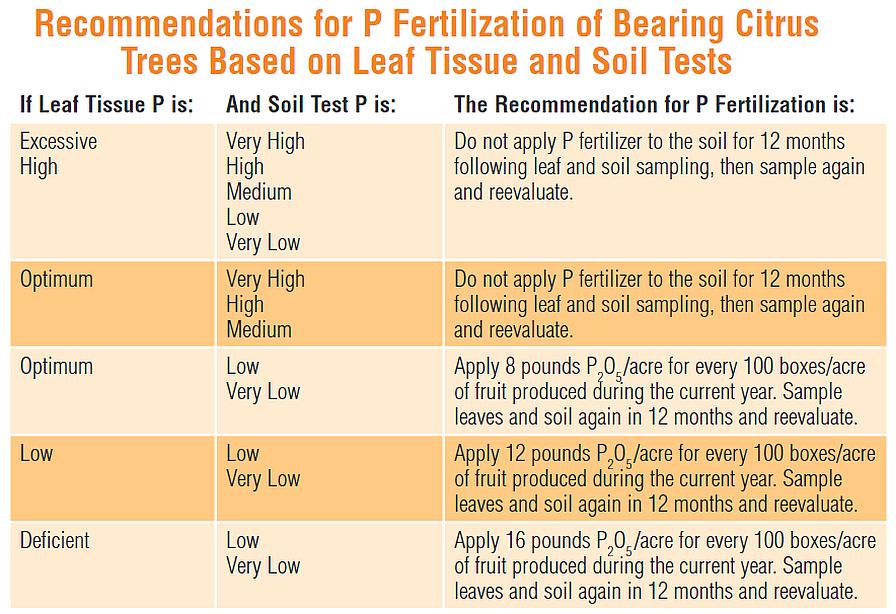

The determination of what level of phosphorus is too high has been the cause of confusion and concern among growers. FDACS confirms its inspectors are “frequently” seeing higher-than-recommended levels (by their standard) in their implementation verification visits to citrus farms. “Producers are required to do soil and tissue tests to justify the use of phosphorus on their groves,” says Erin Moffet, an FDACS spokesperson. “In almost every case, the soil and tissue tests indicate that no phosphorus is needed, yet it is being applied at various rates depending on the operation.” That’s where the rub comes into play because growers contend phosphorus is an element that needs to be maintained at sufficient levels by applications. If they wait until levels are allowed to drop to below optimum levels — enough to show up in testing — it will already be causing damage to the trees. “Phosphorus plays a big role in citrus plant health,” says Ray Royce, Executive Director of the Highlands County Citrus Growers Association. “Certainly, phosphorus is playing a bigger role in tree health than it did before HLB came along. Growers tell me you have to keep phosphorus in a certain range to keep your trees healthier, and that is something you have do to over time. Our concern is if you wait to get below that optimum range, the stress on trees will be greater, and it will take too long to correct.” While there is no specific standard or level for phosphorus stated in the citrus BMP manual, FDACS is referring growers to the 2021-2022 Florida Citrus Production Guide — page 87, Table 7 to be exact. “In the first couple of citrus BMP manuals, phosphorus was not even mentioned,” Royce says. “The current manual does not require growers to meet any specific standard or level when it comes to phosphorus. FDACS would argue that, by inference, growers should refer to the guidance in the citrus production guide, but that’s not stated in the BMPs. I am not sure I agree with FDACS on the inference, and the growers I represent have concerns about that.”

FDACS refers these phosphorus rate recommendations to growers during citrus BMP verification visits.

Source: 2021–2022 Florida Citrus Production Guide: Nutrition Management for Citrus Trees

More Research Needed

With the scrutiny being placed on phosphorus levels, attention has turned to the available research on appropriate rates for use in citrus production. Research conducted by UF/IFAS is what the BMP manual recommendations are based upon. The research that developed the recommendations for phosphorus applications is several decades old. Phosphorus has not been a research priority, like nitrogen, because it is not as mobile and prone to leaching into the waterways. That is reflected in the relatively scant mention of phosphorus in the BMPs. However, that emphasis has changed in recent years due to phosphorus being a major contributing factor to water quality issues. “The current manual simply tells growers to ‘base their phosphorus fertilization rate on soil and/or leaf tissue test results and to keep all lab test results to track changes over time,’” says Bert Harris III, a grower currently serving as

Highlands County Citrus Growers Association President. “It does not set limits or direct growers to follow any specific UF/IFAS guidelines like it does with nitrogen.” Royce and others question if the recommendations in the production handbook are even accurate any longer because they are based on such old research — before HLB arrived. Growers are calling on new research to make informed, science-based guidelines for phosphorus applications — certainly if that is the standard by which they will be regulated.

Kelly Morgan, a Professor of Soil Fertility and Water Management with UF/IFAS, is on the committee updating the current citrus BMPs. He says more research is needed. “We have not really looked at phosphorus that closely, because we felt like we were using so little of it,” Morgan says. “We started some [HLB-infected] rate studies on nitrogen in 2017 and are getting some really good information from that. But that will take a couple more years before we can determine if we need to go up on nitrogen recommendations. As for phosphorus, we clearly are going to need to start working on this area of research as well.” While new research is being conducted, FDACS must work with research currently on hand. “In implementing its regulatory program as required by law, OAWP relies on the best available scientific and technical data provided by UF/IFAS and other research partners,” Moffet says. “As phosphorus rates are focused on production yield and not environmental impacts (per UF/IFAS), and OAWP is tasked with balancing production with water quality improvement, OAWP focuses on maximizing efficiency in nutrient management through precision practices where sustainable rates are unavailable.” People close to the issue expect action could be taken during the 2022 state legislative session to clarify legal language in SB 712, and BMPs in general, and seek monies to fund new phosphorus research. Royce says the research should focus on various production regions and systems because phosphorus acts differently in different settings. “There needs to be a lot of research done in cooperation with growers and UF/IFAS,” he says. “And the recommendations for phosphorus may need to be tailored to growing regions. If you are on the Flatwoods, and materials have a better chance of runoff into surface water, it is going to be different than on the Ridge where the chances are a lot less.” What does all of this mean for the new citrus BMP manual currently in development? It seems all parties involved have hit the pause button for a bit to assess the phosphorus situation. Royce says that’s a good thing. And UF/IFAS, FDACS, state lawmakers, growers, and citrus associations are looking for ways to best facilitate and fund phosphorus research.

Photo by Frank Giles

The Fruit Drop Factor

The current UF/IFAS recommendations are based on yield expectations in a grove. When phosphorus is recommended, it is by pounds per 100 boxes per acre. With fruit drop a common and significant problem in groves, the application math is difficult because the 100 boxes that start on the tree could end up on the ground before the end of the season. FDACS regulators note those fruit on the ground become compost and return nutrients, including phosphorus, back into the soil.