Scientists throughout the South are using artificial intelligence (AI) to help growers save labor costs and time, spray with precision, detect diseases, control food quality, maintain animal health and help grow wheat.

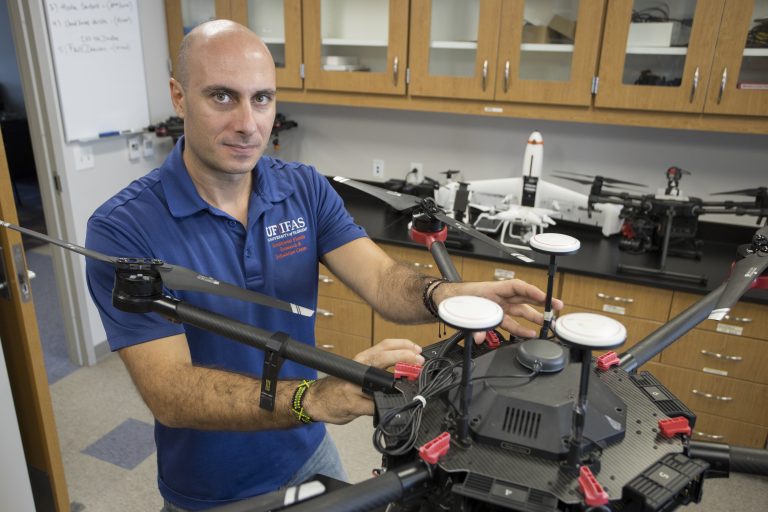

Among the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) scientists helping growers save time and money is Yiannis Ampatzidis, an associate professor of agricultural and biological engineering. Ampatzidis invented Agroview, technology that uses images from drones, satellites and the ground.

Agroview assesses plant stress, and it counts and categorizes plants based on their height and canopy area. The technology also estimates plant-nutrient content. It can reduce data collection, analysis time and cost by up to 90% compared to the manual data collection, Ampatzidis said.

“Growers in Florida and across the United States use this technology to predict yield, to detect stressed plant zones earlier and to develop maps for precision and variable-rate fertilizer applications,” said Ampatzidis, a faculty member at the Southwest Florida Research and Education Center. “The maps can help growers apply fertilizers optimally, reduce application cost and reduce environmental impact.”

Killing Weeds, Not Crops

Weeds can crowd out growing crops. But sometimes, when farmers spray herbicides or fungicides to kill the weeds, they end up damaging crops as well. That’s why UF/IFAS scientist Nathan Boyd devised a precision weed sprayer.

Boyd, a professor of horticultural sciences at the UF/IFAS Gulf Coast Research and Education Center (GCREC), worked with Arnold Schumann, a professor of soil, water and ecosystem sciences at the Citrus Research and Education Center, to design the sprayer.

Boyd uses images of weeds to train computers to identify them. Growers can use those pictures to know when, where and how to control pests. Using this form of precision agriculture, data from Boyd and Schumann have helped farmers reduce pesticide use by up to 90%.

At Virginia Tech, researchers are also interested in identifying and vanquishing weeds without harming crops.

U.S. growers spend approximately $6 to $8 billion annually using herbicides, in addition to rising labor costs for specialty crops.

Vijay Singh, assistant professor in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and Virginia Cooperative Extension specialist at the Eastern Shore Agricultural Research and Extension Center, is leading a project to automate the process of drone-spray technology and machine learning to conduct real-time weed detection. The project aims to standardize the process and bring drone technology to the farmers’ field, saving time and money.

“Testing of unmanned aerial systems is the first step, but the overall goal of these technologies is to automate the process and conduct real-time weed detection and spray applications, which we will achieve in the next few years,” Singh said.

At Virginia Tech, scientists employ machine-learning and image-processing techniques that help growers effectively identify and distinguish between several types of weeds, map their precise locations and conduct real-time weed detection.

UGA CAES Develops Fresh Food Tech with Augmented Reality

Christopher Kucha, an assistant professor of food processing and engineering and head of the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences (CAES) Precision Food Systems Lab, uses precision sensing technologies and AI to create digital technologies including “digital twins” and augmented reality for food processing and quality control.

A digital twin is a virtual model of a physical object, like a food item, that researchers can use to simulate its life cycle and assess production processes.

“Amazon now uses augmented reality programs to show people what the products they are buying might look like in real life, and we are doing something somewhat similar with our digital twins,” Kucha said. “We collect data on a piece of food, its processing operations, distribution and shelf life and then develop the digital counterpart of those processes or products to optimize unit operations and quality monitoring in the supply chain.”

Ebenezer Olaniyi, a graduate research assistant in Kucha’s lab, added that the imaging system should improve the sustainability of the food industry by setting standards for better, faster processes that cut down on costs and waste.