By Ruby Tiwari and Ramdas Kanissery

Yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus) and purple nutsedge (Cyperus rotundus) are perennial weeds that resemble grass. They commonly appear in raised bed vegetable plasticulture systems every year. These weeds spread and reproduce through rhizomes, bulbs and small tubers called nutlets. Just one tuber can generate hundreds of shoots, forming a dense patch that can span 3 to 6 feet. In turn, these shoots produce over 1,000 new tubers. If not properly controlled, these weeds can cause significant crop yield losses.

IDENTIFICATION AND GROWTH

While nutsedges may resemble grasses, they are not actually grasses but true sedges. They have thicker and stiffer leaves compared to most grasses, and their leaves are arranged in sets of three at the base.

Purple nutsedge has dark green leaves, purple to red-brown flower heads, dark-brown seeds and tubers that form chains along the rhizomes (Figure 1). Purple nutsedge can grow up to approximately 50 centimeters in height and is particularly troublesome in tropical and warm-temperate climates, including the Southern United States.

Photo by Ruby Tiwari

Yellow nutsedge has bright green to yellow-green leaves, golden-yellow flower heads, light brown seeds and tubers that are borne individually at the tips of short rhizomes (Figure 2). This weed is found throughout the United States and tends to cause problems in moist or irrigated soils.

Photo by Heather Kirk-Ballard, Louisiana State University AgCenter

MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

Nutsedges are the most challenging weeds in Florida’s vegetable plasticulture. They pose a problem because there are limited herbicide options available, their tubers are difficult to reach, and they can penetrate plastic mulches. Once the rhizome develops, nutsedges can quickly spread beneath the plastic mulch (Figure 3). They cause yield losses in various vegetable crops grown in the Southeast, including cucumber, radish, lettuce, onion, tomato, bell pepper and eggplant. Therefore, the best approach to tackle nutsedge is to prevent its establishment from the beginning.

Photo by Ramdas Kanissery

CULTURAL PRACTICES

Controlling the production of tubers is crucial for managing nutsedge. To achieve this, it’s important to remove young nutsedge plants before they grow to five or six leaves because they haven’t formed new tubers yet. Continuously removing the shoots will deplete the energy stored in the tuber. However, mature tubers have the ability to resprout multiple times. Although these new sprouts initially appear weaker, they can develop into new plants and produce more tubers if not removed.

The most effective way to remove small plants is by pulling them out using a hand hoe. To ensure complete removal of the plant, it is important to extract the nut located 6 to 12 inches below the surface. Repeatedly tilling small areas before nutsedge plants grow six leaves can help decrease their numbers. However, using a tiller to remove mature plants may make the problem worse by spreading the infestation and scattering the tubers throughout the soil.

Drying

One way to control nutsedge is by cultivating the affected areas and then refraining from watering them, which allows the tubers to dry out in the sunlight. However, achieving effective control requires repeated cultivation and drying. It’s important to remember that this method is most effective during fallow periods or in areas where irrigation is not needed. This drying approach is effective for controlling purple nutsedge but not for yellow nutsedge.

Shading

Nutsedges don’t thrive in shaded areas, so planting cover crops that provide shade can help decrease their growth. For example, if a farm has a significant nutsedge problem, using a tall and dense cover crop during periods of no cultivation can effectively prevent nutsedge from germinating and forming tuber banks in the soil.

Mulching

A key approach to managing nutsedge is to maintain a mulch cover over raised beds. While commonly used plastic mulches made of polyethylene do not offer complete control against yellow or purple nutsedge due to their sharp tips easily penetrating the plastic, plastic mulch may possibly help reduce the number of nutsedge plants.

CHEMICAL CONTROL

Cultural methods alone are often not enough to effectively manage nutsedge in vegetable production systems. Chemical control is typically necessary for better results. Fumigants are an option, but the phase-out of effective fumigants like methyl bromide has made nutsedge control inconsistent and unreliable, often requiring a combination of herbicide application under the plastic mulch. However, only a few herbicides are truly effective against nutsedge, as some may not be absorbed by the tubers or may have reduced tolerance in crops.

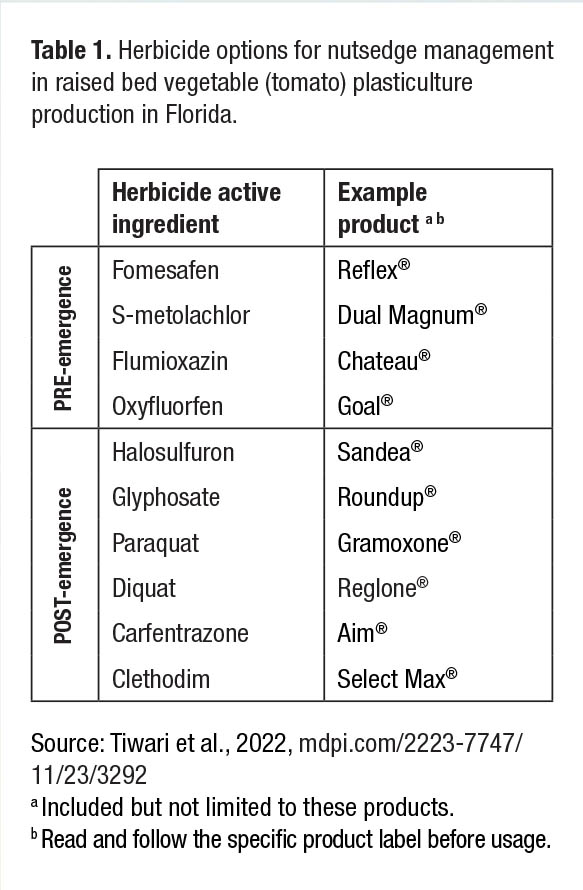

Pre-emergent herbicides can be applied before weed emergence in bare soils or raised beds. Examples include fomesafen (Reflex®), S-metolachlor (Dual Magnum®), flumioxazin (Chateau®) and oxyfluorfen (Goal®). For nutsedge that emerges after crop establishment, post-emergent herbicides like halosulfuron (Sandea®), glyphosate (Roundup®), paraquat (Gramoxone®), diquat (Reglone®), carfentrazone (Aim®) and clethodim (Select Max®) can be used.

While pre-emergent herbicide application under plastic mulch can reduce the need for in-season nutsedge control, its effectiveness is temporary and inconsistent. One challenge is the loss of active herbicide ingredients from the soil’s weed seed germination zone over time. To achieve season-long nutsedge control, a recommended approach is to combine pre-emergent herbicides with carefully planned post-transplant herbicide application. Table 1 presents the common pre- and post-emergent herbicides used to control nutsedge in Florida’s tomato production.

See mdpi.com/2223-7747/11/23/3292 for additional information on weed control in plasticulture production.

Ruby Tiwari is a Ph.D. graduate student, and Ramdas Kanissery is an assistant professor, both at the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Southwest Florida Research and Education Center in Immokalee.