By Brad Buck, (352) 875-2641, bradbuck@ufl.edu

Fumigants are an essential tool growers implement before planting to manage soil health. They reduce harmful diseases such as Fusarium wilt and pests like root-knot nematodes and weeds that compete for water and nutrients. Their effect on soil diseases, pests and weeds help sustain production.

But how does it happen, especially considering there’s so much underground. A teaspoon of soil can contain more than 4 billion microbial organisms, including bacteria, fungi, protozoa and nematodes.

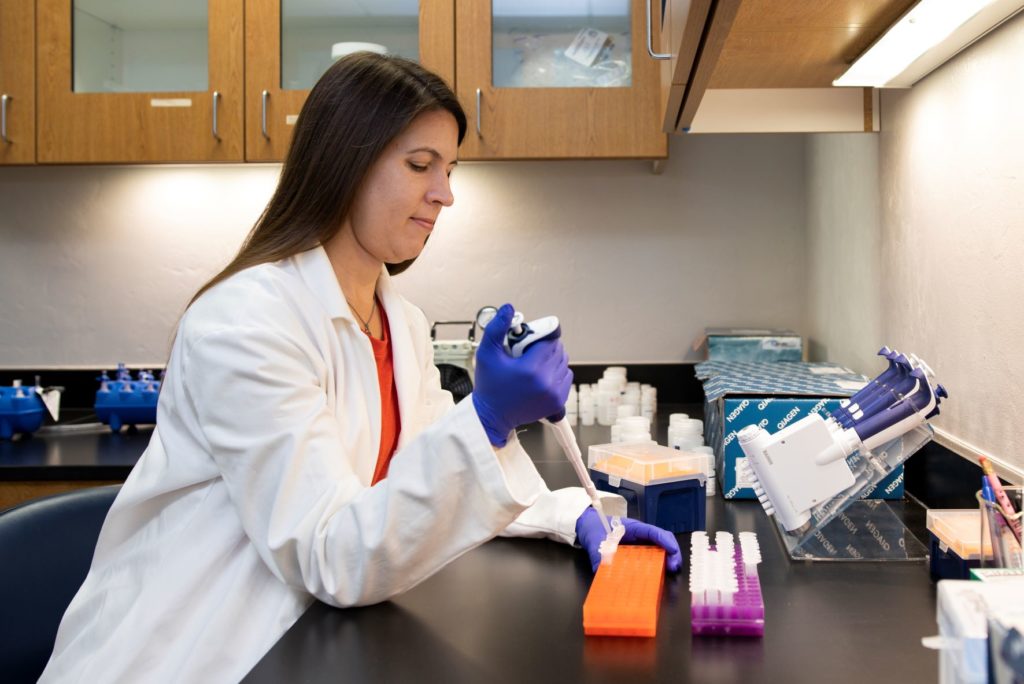

University of Florida (UF) soil microbiologist Sarah Strauss received an $850,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture to study how fumigation impacts the soil microbiome. Farmers could manage soil health more efficiently.

“We know that fumigants are pretty good at reducing the ‘bad’ soil microbes – the ones that cause diseases,” said Strauss, an assistant professor of soil and water sciences at the UF Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS) Southwest Florida Research and Education Center.

“We don’t really know what happens to all the other microbes in the soil when these fumigants are applied. But since the fumigants hurt the pathogens – the ‘bad microbes’ — they might hurt the other microbes. These other microbes include ones that could be helpful for plants.”

For example, soil bacteria and fungi help nitrogen cycle through the soil and prevent soil-borne diseases from infecting plants. Soil fumigants also impact weed germination, but scientists don’t know how fumigants impact weed populations over multiple growing seasons.

“We want to try and figure out if the ‘good’ soil microbes are still around after fumigation and are helping this process — or not,” said Strauss. “We need to better understand what’s happening in the soil before we can try and optimize or improve these fumigation practices.”

The more data Strauss and her colleagues can pass along to farmers about soil fumigation, the better the odds producers will grow more tomatoes and strawberries.

Strauss is collaborating with Nathan Boyd, a professor of horticultural sciences; Gary Vallad, a professor of plant pathology; and Mary Lusk, an assistant professor of soil and water sciences – all of whom work at the Gulf Coast Research and Education Center (GCREC).

They’ll conduct their research at GCREC and at commercial tomato and strawberry farms, most likely in Hillsborough County, the home of many Florida strawberry farms.

Throughout Florida, fresh market tomatoes generate about $400 million a year, while strawberries, bring in about $300 million.