By Kimberly L. Morgan, Xiuri Cui and Zhengfei Guan

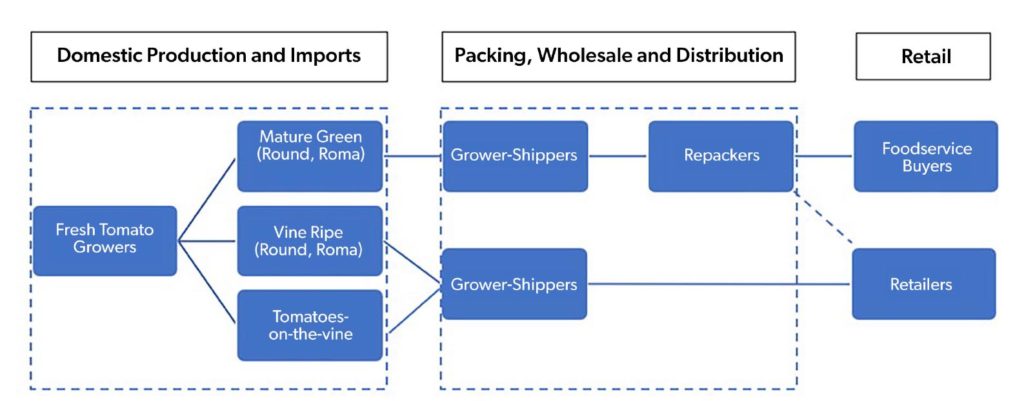

Driven by consumer demand, the fresh tomato supply-chain network includes product harvested at different maturity stages, resulting in a unique marketing process distinguishable from other produce. Fresh tomatoes are typically marketed either through retail or foodservice channels. From farm to fork, the supply chain is divided into stages with different entities:

- Production (domestic and imports)

- Intermediaries engaging in the activities of packing, repacking, wholesale and distribution

- Retail, involving retailers and foodservice buyers

Grower-shippers are growers that engage in production, packing, shipping and selling. A repacker is a wholesaler that operates in ripening, resorting and repacking mature green tomatoes into uniformity according to the timing and needs of customers, particularly the foodservice buyers such as the fast-food chains. Foodservice buyers and retailers often contract with distributors to manage the shipping logistics. This article discusses trends affecting profitability of the Florida tomato industry within each segment in the fresh tomato supply chain (Figure 1).

TOMATO TYPES

Most Florida-grown tomatoes are harvested at the mature green stage, which the foodservice sector prefers for better slicing characteristics. Vine-ripe tomatoes are harvested at the ripening stage. Tomatoes-on-the-vine are primarily grown in protected structures and packaged directly after harvest. This results in a higher quality product with extended seasons, which is preferred by the retail market for better appearance, taste and year-round availability. Roma tomatoes can be produced in the open field and in protected systems.

Driven by the increase in consumers’ awareness of health and wellness and willingness to try different varieties of tomatoes, some growers are expanding their offerings to include specialty tomatoes and snacking types.

CONSUMER CONCERNS AND AVAILABILITY

In a survey of southeastern U.S. tomato buyers, fresh produce consumers reported they are more concerned about the safety of U.S. foods relative to U.S. food price trends (Maples et al., 2018). Researchers also noted that people are searching for food relationships in response to diet-related disease incidences in themselves and their family members (Thapaliya et al., 2017) But are they really?

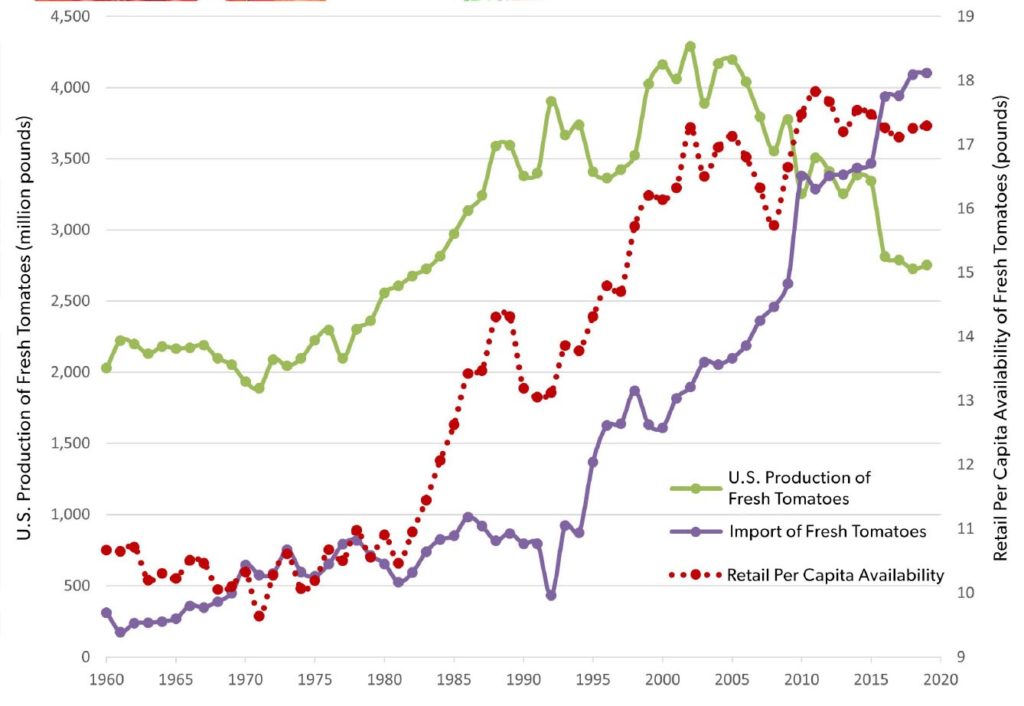

Retail per capita availability of fresh tomatoes (America’s second most popular vegetable) was examined to answer this question. Since 1996 (just after Canada, Mexico and the United States signed the North American Free Trade Act), per capita availability of fresh tomatoes (field and greenhouse, domestic and imported sources) hovered between 16 and 17 pounds per year, up from about 11 pounds per person in 1960 (Figure 2).

CONSUMPTION AND COSTS

The 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends an average adult may consume 2,000 calories per day and suggests a well-balanced diet that include 2 cups of fruit and 2.5 cups of vegetables. U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) food consumption surveys find that the average American falls far short, consuming only 0.9 (45% of recommended volumes) cups of fruit and 1.4 (56%) cups of vegetables per day.

Are vegetables cost-prohibitive? Using the average vegetable price of $0.80 per cup and multiplying by the recommended 2.5 cups per day for a healthy diet, the cost of including vegetables in a healthy diet is equal to $2.00 per day, about 20% of the average daily food cost of approximately $10 per person (USDA, Economic Research Service).

It is important to note that people are paying prices that are 1.72 times higher than average prices since 2000, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index. This is another factor influencing consumers’ choice of foods to purchase either at home or away from home.

Given the relatively stagnant consumer demand for fresh tomatoes, the swap in volume between domestic production and imports is expected due to advantages observed in importing countries. U.S. growers in Florida and California continue to lose market share to Mexico (due in part to relatively higher U.S. farm labor wages and overlapping seasonal production) and Canada (greenhouse production). This has resulted in reduced numbers and consolidation among Florida’s growers.

Over the past two decades, shipping point prices reported by the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service are trending upward. However, costs of production increased significantly since 2020 due to global shocks including the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Record high prices are being seen for phosphorus, nitrogen, potash, cardboard boxes, wooden pallets and irrigation supplies.

CHALLENGING CONDITIONS

Truck driver shortages remain the biggest issue in distribution and transportation and have become even more challenging in recent years. In early 2022, Florida reported the highest truck shortages relative to its competitors, driven mainly by too few drivers and rising fuel costs. This provoked companies to invest heavily in technology innovation to enhance logistical efficiency and preserve safety and quality of its fresh produce.

With the ongoing macroeconomic shocks exposing the vulnerability of the global fresh produce supply chain, it is important to understand the complexity of the U.S. fresh produce network. U.S. fresh tomato consumption has remained relatively steady over the past two decades, and adjustments across the structure of the industry may be required to meet changes in buyer demand for America’s second-favorite vegetable. The COVID-19 pandemic disruption and pressure from the retail sector to keep consumer prices low under rising inflationary conditions negatively affected demand for Florida’s tomato growers, the largest supplier of open-field mature green tomatoes in the United States.

Increasing foreign competition, labor shortages, and rising input costs continue to impact grower profitability. Addressing these issues individually is not expected to increase long-term industry competitiveness. Rather, improved understanding of the roles and dynamic interactions among supply-chain participants is needed. This could help policymakers, researchers and stakeholders make better-informed decisions to improve industry coordination and competitiveness, expand U.S. market demand and build supply-chain resiliency.

Kimberly L. Morgan is an associate professor at the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) Southwest Florida Research and Education Center in Immokalee. Xiuri Cui is a Ph.D. candidate at UF in Gainesville. Zhengfei Guan is an assistant professor at the UF/IFAS Gulf Coast Research and Education Center in Wimauma.

Cutlines: