Glenn Beck (pictured) and his brother, Mark of Beck Bros. Citrus, own and caretake for about 7,500 acres of citrus in Florida.

Photo by Frank Giles

When Glenn Beck and his brother, Mark, were kids, the surroundings of his family’s farmstead were dominated by citrus groves and sandy clay roads. Today, the location is surrounded by suburbia only a few miles from Disney’s Magic Kingdom. The freezes in the 1980s took out the groves, and urban growth filled the spaces left behind. But the Becks are still going strong in their fourth generation of farming in Windermere and various other locations across the state.

Diversification has helped sustain the agricultural business over the years. In addition to its primary citrus crop, the farm produces blueberries, greenhouse ornamentals, and cattle. They also own and operate a tree caretaking operation. Between their own groves and those they care for, the brothers are managing about 7,500 acres of citrus.

Adjusting to HLB

Just like the freezes and growing urbanization, HLB has changed the very nature of citrus production in Florida. But Glenn Beck says it can be grown successfully even in the presence of HLB, which is now endemic across the state.

“From the beginning of HLB to this day, you will hear people say, ‘It doesn’t make economic sense to plant citrus,’” he says. “We’ve always felt just the opposite. As HLB began to spread, there were a lot of recommendations to do all these different things in response to the disease that many growers could not afford. It was kind of an all-or-nothing mentality.

“My advice was to do what you can afford and stay engaged if at all possible. You might not bring every tree through HLB, but a lot of them, you will. It is as much about the passage of time as it is all of the inputs you apply to a grove.”

Having groves in both the southern and northern parts of the state, Beck has seen the importance of the time factor and HLB. Groves further north were virtually untouched in the early days of the disease, while groves in the south went downhill fast. Eventually, the disease spread north with the same results. Beck is among those who believe trees almost have to decline before coming back with rehabilitation production practices.

“We took preventative measures that kept our groves in the north highly productive and delayed the inevitable as HLB spread,” he says. “The production would have fallen off much sooner had we not. Also, we’ve seen groves that were hit hard early in the south start to recover. We’ve seen significant recovery in some of our blocks. The analogy I use is HLB is a like a cold. You feel it coming on but know there’s nothing you can really do about it. So you power through it and come out the other side feeling better.”

The Becks are doing many of the same things other growers are doing to make the HLB-infected trees feel and perform better, with plant nutrition being a central player. They are spoon-feeding fertilizer to the roots via more frequent irrigation. They are applying other nutritional products to keep trees well fed, but at doses the roots and foliage can absorb efficiently. Resets are given a head start with slow-release fertilizers. The key, Beck says, is getting on a good, basic production program and sticking with it to allow time for trees to respond.

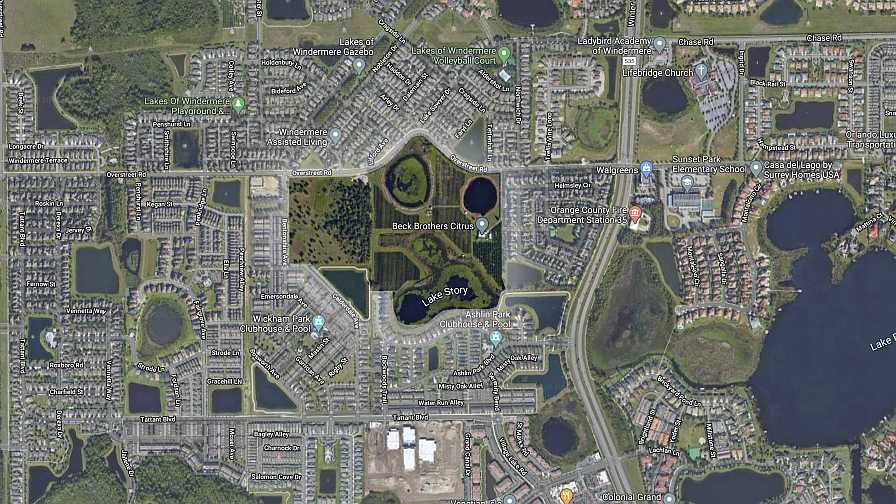

While Beck Bros.’ original farmstead is surrounded by the city, they have grove locations throughout the state.

Image courtesy of Google Earth

Keep Planting

HLB has not deterred Beck Bros. from planting. Trees are being reset as they age and decline out of production. Some new blocks have been planted as well since the disease came along. Round oranges on US802, US942, US812, and Swingle rootstocks have been the go-to selections.

“When HLB started to spread and we realized how bad it would be, some people decided they were not going to plant until some breakthrough treatment or resistant tree came along,” Beck says. “Well, 15 years later, those folks are still waiting. We need to plant trees today. This industry has gotten too small to supply our juice demand.”

He says the aftermath of Hurricane Irma showed what imported juice can do to crash the market and prices. Planting trees and increasing production at competitive, sustainable prices, combined with marketing to grow consumption, are keys to the future of Florida citrus.

“We believe it’s something that can be done, and we’ve approached our business that way ever since HLB came along,” Beck says. “With COVID-19, consumers are reminded that orange juice is a healthy drink, so we are enjoying more citrus [inventory] movement and hopefully will see a better market and prices this season.”

Some of the farm’s blueberry U-Pick customers cross the street or ride their bikes to the 20-acre planting in Windermere.

Photo by Frank Giles

Blueberries Add Diversification to the Farm

In 2009, Beck Bros. added blueberries to its portfolio. Initially, the crop was grown for the commercial fresh market. But as Mexican blueberry imports flooded into the U.S. in the middle of Florida’s harvest window, the economic viability of commercial production declined. Being surrounded by urban sprawl, the 20-acre blueberry field on the farm is perfectly positioned for U-Pick. Several years ago, the family decided to switch over to U-Pick only. It was a fruitful decision. On busy weekends, upward of 2,000 people visit the farm.

“We literally have customers that walk across the street or ride their bikes to the farm,” Glenn Beck says. “Our U-Pick is a no-frills affair. We don’t have the bounce houses and the other side things going on, but there is a segment of the population that gravitates to our quieter, more simple experience. We just sell blueberries and honey and have enjoyed success.”

The 2020 season coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, but it didn’t hurt business. In fact, Becks says they had a better season than normal under the shutdown.

“We added more wash stations for sanitation, and there is plenty of room for folks to socially distance in our field,” he says. “There was a pent-up demand to get out and do something, and this was a safe place to do it while picking a healthy fruit.”