The first chore for growers in the cold-hardy citrus region when managing citrus greening is scouting for the disease and its vector, the Asian citrus psyllid. The next step is prompt removal of any trees infected with the disease, says Jonathan Oliver, University of Georgia (UGA) assistant professor and small fruits pathologist.

“At this point, we think greening is still at a low enough level in Georgia that this would be the major thing to do — getting rid of these trees so they will no longer serve as sources of new infection and also to spray and treat populations of the psyllid. That would be the other remedy right now,” Oliver advised.

HLB was observed in a Georgia commercial grove for the first time in 2023, a key development for an industry still growing in the cold-hardy citrus region that includes North Florida, South Georgia and South Alabama.

“Once greening becomes established, and a huge percentage of the trees become infected like they are in Florida, growers have to use different techniques, which basically is managing the effects of the disease rather than trying to deal with the actual disease itself. A lot of energy in Florida citrus operations goes into reducing spread, yes, but also fertilizing and maintaining these trees so they can still produce,” Oliver said. “We’re not at that stage, and I don’t want us to get to that stage, so early intervention is very important. This means removing infected trees and then treating psyllid populations if they’re present.”

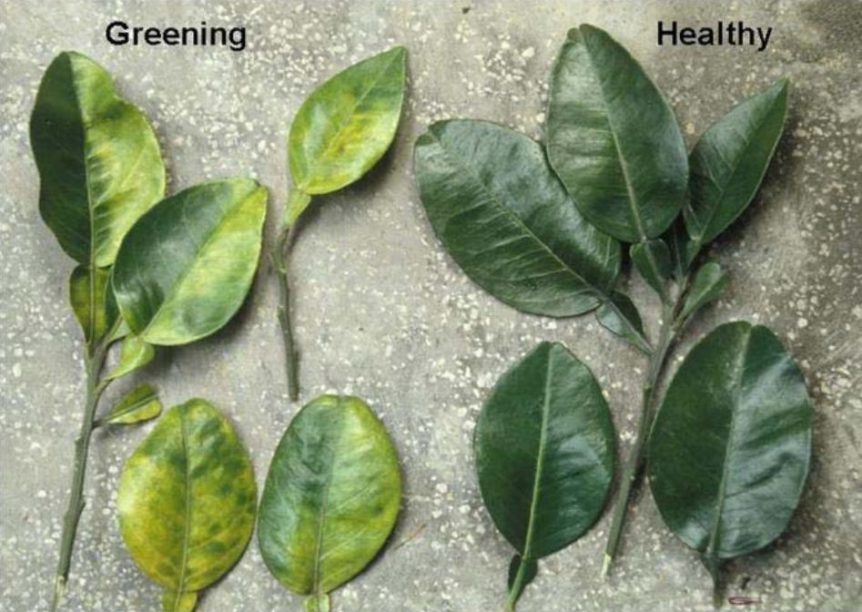

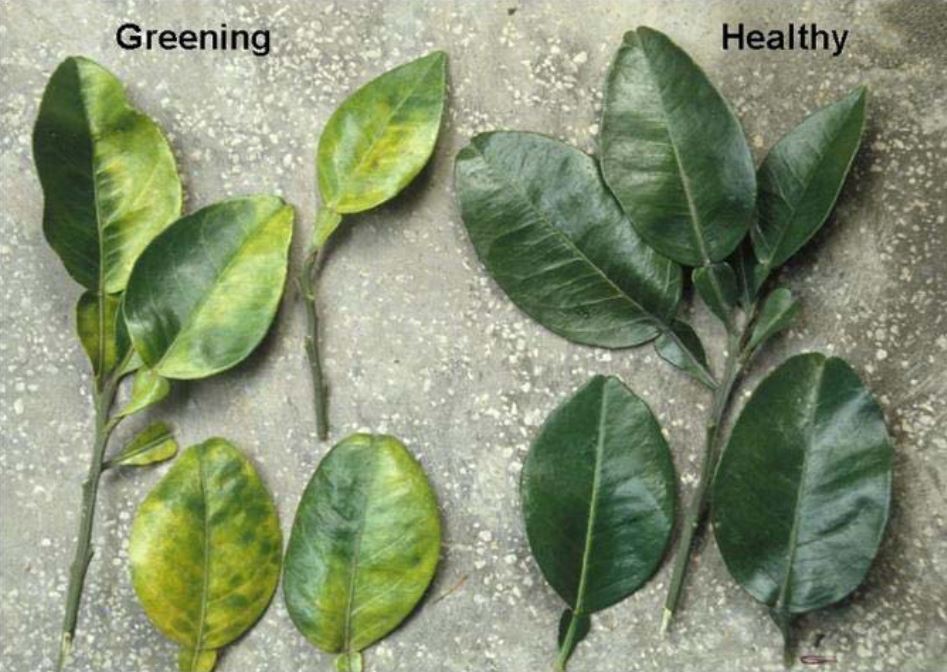

According to the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, citrus greening, also known as huanglongbing or HLB, affects citrus production across the globe. Symptoms include asymmetrical yellowing of the leaves and leaf veins. Later symptoms include twig dieback and decreased yields. Fruit is often small, lopsided and not marketable. Fruit drop can also occur as a result.

By Clint Thompson