By Pam Knox

Georgia is known as “The Peach State,” but the production of blueberries is a much bigger contributor to the state’s economy than peaches. However, both types of fruit have one thing in common. They are being affected by the trend toward warmer temperatures that are being seen across the world due to increases in greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

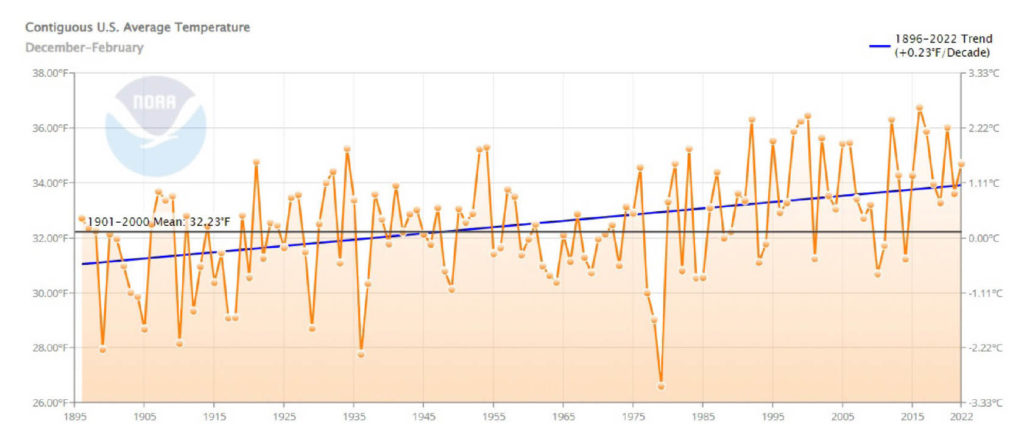

In the United States, winter temperatures have risen by about 3 degrees Fahrenheit since records began in 1895 (Figure 1). In fact, winter is warming faster than any of the other seasons. This is because snow and ice cover, which reflect sunlight away from the earth before it can warm up the ground, are shrinking as the temperature gets warmer. That means more energy from the sun can warm up the ground or ocean and the atmosphere over it, which leads to more snowmelt and a further increase in temperature.

Source: www.ncei.noaa.gov/cag

LESS CHILL HOURS

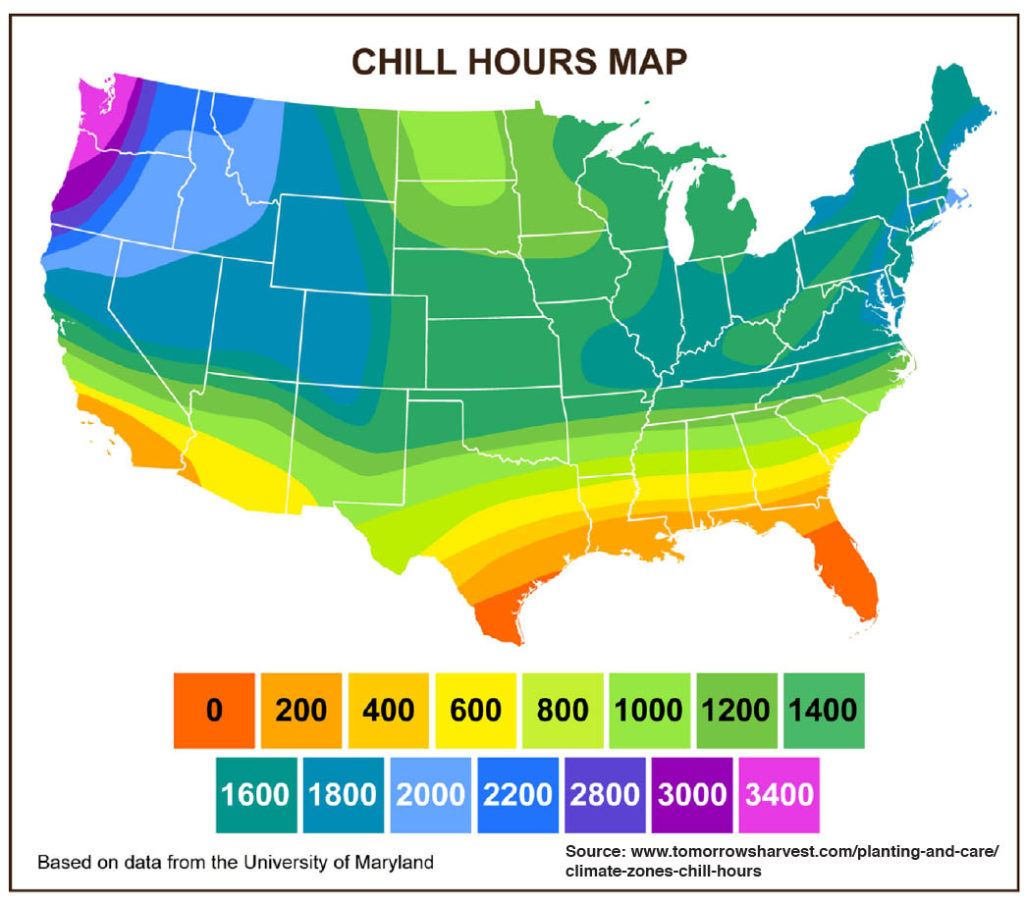

Warming in the winter months is especially detrimental to fruit production because it reduces the number of chill hours that dormant plants experience. Chill hours are a measure of how long the fruit trees and bushes experience cold temperatures over the course of the winter.

Chill hours are calculated in several ways. For example, one common version of chill hour accumulation counts the number of hours that the temperature is below 45 degrees. The hours are usually added up starting on Oct. 1 or Nov. 1 and can range from 200 chill hours in northern Florida to 1,400 chill hours in Michigan in the fruit belt along the eastern shore of Lake Michigan. The northwestern corner of Washington may get over 3,000 chill hours per year.

If plants don’t get the chill hours they need, the number of blossoms produced in the spring is reduced or the blooms do not come out evenly. Therefore, the yield of fruit is also reduced. Plants could bloom late, sometimes as much as a month or even two later than usual, and leaf development also could be delayed.

Even if plants do get enough chill hours over the winter, they may still experience problems if a warm spell comes early in the spring. In that case, the plants are ready to break dormancy, and the spring bloom can occur earlier in the year than in past seasons. This makes plants more susceptible to a late freeze. In the past few years, several warm winters followed by a late frost have caused severe loss of fruit in the Southeast that has significantly impacted farmers.

COPING METHODS

Fortunately, there are methods that farmers can use to cope with the warmer winters. Peaches, apples, blueberries and other fruit come in many varieties with different requirements for chill hours. Therefore, farmers planting new orchards can pick a variety that works with the current climate as well as one that might be a bit warmer in the future.

Those with orchards that are already planted can delay bud break by using chemical sprays or pruning to select branches that have buds with the lowest chill hour requirement.

Frost protection methods for orchards that are already blooming can be utilized to protect the buds. Methods include using water for irrigation, helicopters or fans to increase air movement of warmer air from above down to the surface, or fires within orchards to keep the temperatures up. But in some cases, frost protection is not enough to keep the buds from freezing, resulting in a partial or (in the worst cases) nearly complete loss of the crop for that year.

Planting multiple varieties with different chill requirements can help spread out the risk of damage from bad weather and climate conditions.

Maintaining good nutrition and protecting against pests and diseases is especially important for trees that have been stressed by either the warmer winters or any late frosts that may have occurred.

While there will continue to be some colder years mixed in with warmer ones, fruit producers should expect winters to continue to slowly get warmer and adapt by choosing appropriate varieties or even switching to different fruit crops that require fewer chill hours. Learning from producers who live in warmer climates can also provide valuable information on crop management.

Pam Knox is an agricultural climatologist at the University of Georgia J. Phil Campbell Sr. Research and Education Center in Watkinsville.