By Mengyi Gu, Hung Xuan Bui and Johan Desaeger

If you happen to travel around Wimauma, Florida, you will see many plastic tunnels and may wonder what they are. Asian farmers (mostly Vietnamese) are using those plastic tunnels to grow a wide variety of specialty Asian vegetable crops.

There is a high demand for these vegetables from northern cities such as New York and Chicago, especially during the winter. In the United States, the demand for ethnic and specialty vegetables is rapidly increasing, and Asian vegetables have become one of the most popular specialty crops. The growing population of Asians, the blooming ethnic cuisine restaurants, and the demand from American consumers for Asian vegetables in their diet has boosted Asian vegetable production in Florida.

The climate in Florida is very favorable year-round for growing many of the popular Asian vegetables. According to the 2019-20 Vegetable Production Handbook of Florida, currently more than 40 Asian vegetables are grown on 8,000 acres across Florida (with an increase of more than 3,400 acres over the past years). Some of the most common Asian vegetables grown in Florida include bok choy, long bean, bitter gourd, Thai basil, Malabar spinach, water spinach and mizuna.

Recommendations for weed, insect and disease management in Asian vegetables have been published in the handbook. However, nematode management recommendations for these specialty vegetables are not available, and few growers are even aware of the existence of nematodes in their fields. Also, most of these ethnic farms are typically small (less than 50 acres), and many of them do not have pesticide licenses due to the language barrier. Because of this, these farmers tend to be isolated and have limited access to pest and disease management information.

WHAT WAS FOUND

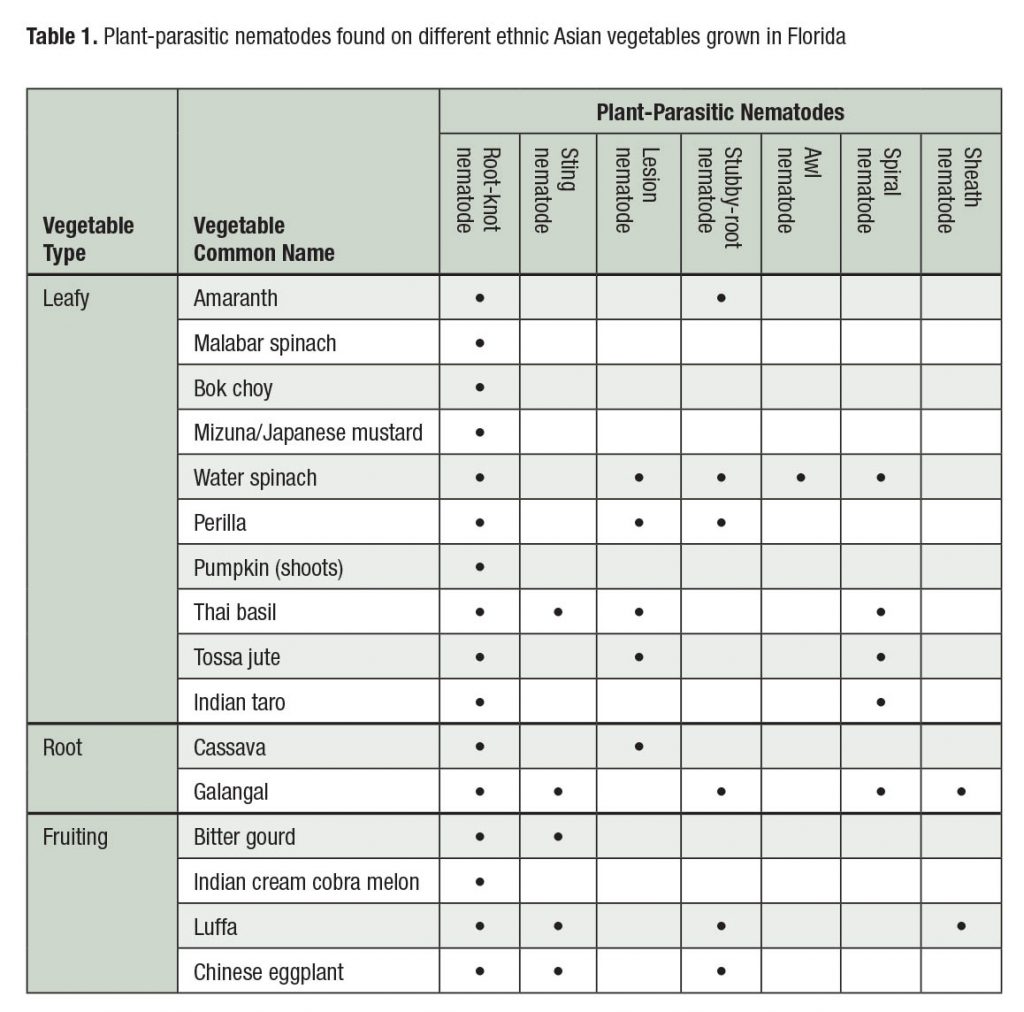

During the past year, postdoctoral associates from the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) Gulf Coast Research and Education Center (GCREC) nematology laboratory led an effort to visit some of the ethnic vegetable farms in Wimauma. The objective was to learn more about the crops that are grown and if nematodes are a problem. Most farmers were unaware of a nematode problem, but results indicated that five of the six surveyed farms did have visible nematode damage in the form of stunted and chlorotic plants. A total of 16 different vegetables were sampled, mostly leafy, but also some fruiting and root vegetables (Table 1).

Root-knot nematodes were the most commonly found and appeared to cause the most damage. Other potentially damaging nematodes that were found were sting, stubby root and lesion nematodes. While it is not known how much damage nematodes cause on these farms, Thai basil, pumpkin, Malabar spinach, Indian taro, sweet potato, jute, bitter gourd, luffa and Chinese eggplant showed visible aboveground symptoms, such as leaf yellowing and wilting.

Plant-parasitic nematodes are microscopic roundworms that feed on living plant tissues. Most nematode species feed on the belowground parts of plants like roots and tubers, although some species feed on aboveground plant parts, which can sometimes be seen on strawberries in Florida. There are no typical aboveground symptoms of nematodes feeding on roots, and often their damage may be misidentified with other causes such as nutrient or water deficiency, or diseases related to bacteria or fungi (stunting, wilting and yellowing).

It is estimated that global agriculture production loses more than $100 billion annually due to nematode damage. In Florida, year-round warm weather and high humidity create a perfect habitat for many plant-parasitic nematodes, and nematode damage can be very severe, especially in sandy soils.

NON-CHEMICAL CONTROLS

Since most Asian vegetable crops do not have a pesticide label, growers must rely mostly on non-chemical nematode management methods. Sanitation should always be the first recourse against nematodes.

Growers should select sites with no or low nematode populations and avoid the introduction of nematodes into the field. It may be tedious, but it is important to clean farm equipment before and after working in different fields.

A common way that nematodes are introduced into fields is through infected plant material (transplants or tubers). While it is generally difficult to recognize whether plant material is infected with nematodes, in the case of root-knot nematodes, the presence of galls or knots on roots of transplants or tubers is a telltale sign. However, nematode galls can easily be overlooked when they are small or when roots are covered with soil. For most other nematodes, no real diagnostic root symptoms can be observed on planting material, and proper diagnosis will need to be done at a nematology lab.

Frequent applications of organic amendments (animal and green manures, compost, etc.) will increase soil organic matter and microbial activity while stimulating natural enemies that may reduce the damage caused by plant-parasitic nematodes.

Crop rotation with nematode poor-host plants could be another option for Asian vegetable growers, but not enough is known now on nematode host status of Asian vegetables to make good recommendations. Planting cover crops in between vegetable crops is a widely adopted nematode-management strategy. For managing root-knot nematodes, sunn hemp and sorghum-sudangrass are recommended as cover crops since they are known to be poor hosts.

The GCREC laboratory can help growers identify if they have nematode problems in their fields. Soil and root samples can be submitted to the laboratory free of charge. For more information, contact hungbui@ufl.edu (English or Vietnamese) or gumengyi@ufl.edu (English or Chinese).

Mengyi Gu is a postdoctoral associate, Hung Xuan Bui is a postdoctoral research associate, and Johan Desaeger is an assistant professor — all at the UF/IFAS GCREC in Wimauma.