By Bhabesh Dutta

The climate prevalent in the Vidalia onion zone (southeastern Georgia) is conducive to many diseases. Among the diseases, those that are caused by bacteria and fungi are the prominent ones. Some of the diseases caused by water molds or oomycetes (Pythium damping-off and downy mildew) can also be seen periodically. Based on my experience as a vegetable Extension pathologist and onion disease specialist in Georgia, I generally see a seasonality to some of the important diseases. This article covers points that relate to disease seasonality and management.

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER PROBLEMS

Onion seeds are sown around mid-September to early October on seedbeds. Some of the diseases that are normally seen during this period are Pythium damping-off and foliar blight caused by Xanthomonas leaf blight and Pantoea sp.

Fungicides labeled for onion are effective against Pythium and can be used as a soil application according to the label. Use of optimum watering and avoiding seedbeds in low-lying areas of the field can also help in managing this disease.

In terms of bacterial blights in seedlings on seedbeds, some growers use copper-based bactericides that are effective. Normally, nature takes its own course. When these seedlings are transplanted in the field, carry-over bacterial disease issues from seedbeds are seldom seen. This is in part due to the cooler conditions that are prevalent during December and January, which these bacterial pathogens do not prefer.

Onion seedlings are transplanted after Thanksgiving or in late November and continue until mid-December. Diseases are not so common during these months; however, Vidalia onion growers use a preventive spray of broad-spectrum fungicides that provides a general level of protection against foliar fungal pathogens.

JANUARY/FEBRUARY DISEASES

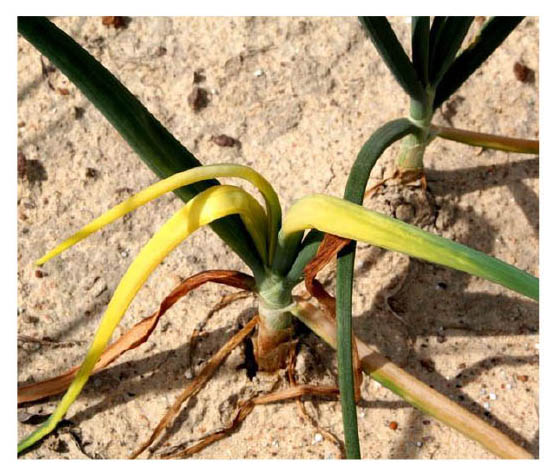

Fungal diseases are rare during December and January, but some bacterial diseases like bacterial streak and bulb rot (causal organism: Pseudomonas viridiflava) and yellow bud (causal organism: Pseudomonas coronafaciens) can be observed in late January to late February. Use of copper-based bactericide spray, optimum nitrogen fertilization and optimum irrigation generally help in managing these diseases.

WHAT TO WATCH FOR IN MARCH

As the temperature becomes moderate in March, along with frequent rainfall, Botrytis leaf blight (causal organism: Botrytis squamosa) and purple blotch (causal organism: Alternaria porri) can be observed. Stemphylium stem blight (causal organism: Stemphylium vesicarium) can also be seen in fields that are infected with either of these fungal pathogens. In general, Stemphylium sp. appears to be a weak pathogen under Georgia conditions, and it generally follows after Botrytis leaf blight, purple blotch or other diseases. A comprehensive fungicide program [as recommended by University of Georgia Cooperative (UGA) Extension] beginning in early March until harvest maturity (mid-April) effectively manages these three fungal diseases.

During the same time, the dreadful downy mildew disease (causal organism: Peronospora destructor) can also occur. Downy mildew is sporadic but aggressive. This disease is favored by prolonged leaf moisture and cooler night temperatures.

The fungicides that are labeled for use on onion against downy mildew are either moderately effective or less effective. Rotation of some of the moderately effective fungicides from different modes of action can help. Management practices that reduce prolonged leaf moisture and promote aeration can also help. The Vidalia Onion & Vegetable Research Center and UGA Extension specialists provide weekly forecasts of conditions that are conducive for downy mildew. These weekly alerts help onion growers to preventively spray against this pathogen.

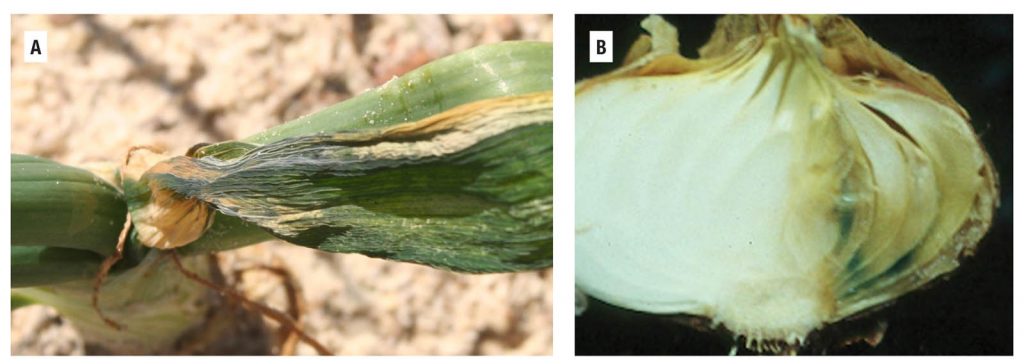

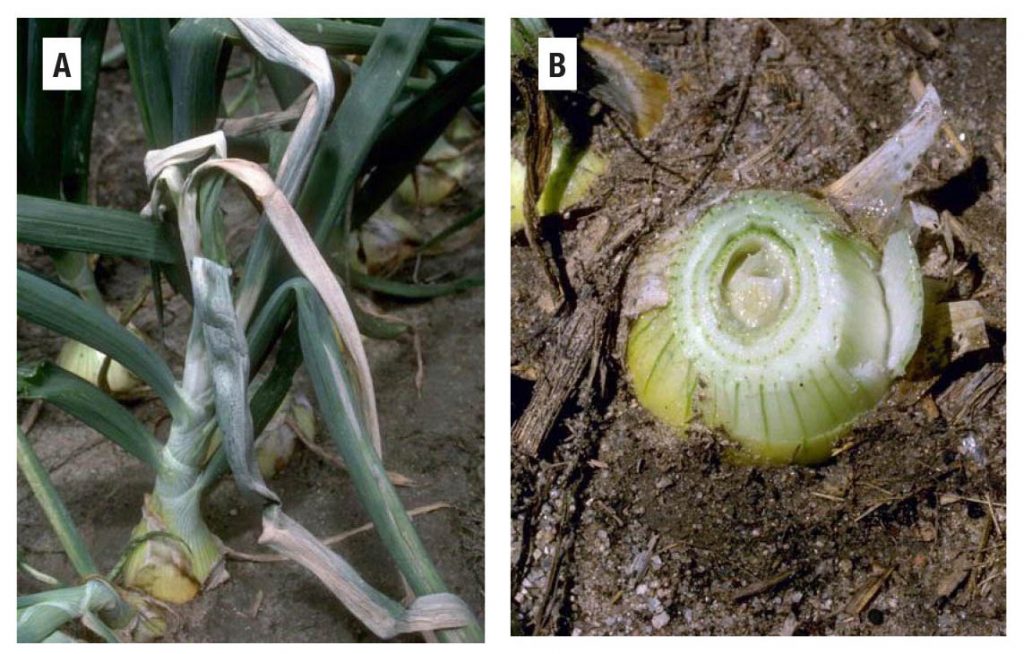

Bacterial diseases appear to be prevalent and problematic during the third week of March to harvest (late April) and can carry-over to storage (cause post-harvest losses). Some of the important bacterial diseases that Vidalia onion growers encounter are center rot (causal organism/organisms: Pantoea species complex), sour skin (causal organism: Burkholderia cepacia) and slippery skin (causal organism: Burkholderia gladioli pv. allicola). Sour skin and slippery skin are generally observed around harvest maturity.

Some of the minor bacterial diseases that can also be seen around harvest maturity are Enterobacter bulb rot/decay (causal organism: Enterobacter sp.), Rahnella bulb rot (causal organism: Rahnella sp.) and Pectobacterium soft rot (causal organism: Pectobacterium sp.).

Center rot outbreaks in Georgia generally coincide with the prevalence of thrips, which usually appear in late March and continue to increase in population throughout the rest of the crop growth period. Pantoea sp. can be acquired and effectively transmitted by thrips and hence, it is postulated that center rot appears in the Vidalia onion region when both thrips and Pantoea sp. are present together. Pantoea sp. can also be seed-borne, but its importance in disease outbreak may not be significant.

The bacterium is also present on asymptomatic weeds as an epiphyte, and in most of the cases, the bacterium in non-pathogenic. However, some of the Pantoea sp. on weeds can be pathogenic on onion seedlings/plants. As far as management of this disease is concerned, an effective weed and thrips management program along with a bactericide spray (program during susceptible onion growth stages) can effectively reduce the incidence and severity of disease in foliage and bulbs.

Sour skin and slippery skin management are quite challenging; in most cases, use of a bactericide program does not seem to effectively manage these diseases. Crop rotation may provide a limited benefit, but due to the pathogen’s natural widespread prevalence in soil, real benefits of this cultural practice are hard to achieve.

Soil amendments with solarization, biofumigants and biocontrol also provided limited benefit, especially for sour skin. The UGA Extension Bulletin on bacterial disease management recommends avoiding overhead irrigation near harvest time. Another critical recommendation is harvesting onion at the optimum level of maturity followed by field curing for a minimum of 48 hours. Infected bulbs should be graded and discarded prior to storage with other healthy appearing onions. Evaluation of cultural practices, nitrogen fertilization, irrigation regimes (type, frequency) and post-harvest treatments are underway with support from the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture Specialty Crop Research Initiative (2019-51181-30013) and the Vidalia Onion Committee grants. Production practices that generally reduce weeds, thrips and/or other insect pests, preventing injury to the foliage/bulb, avoiding over-irrigation, along with diligent use of a fungicide and bactericide spray program will help manage these diseases.